The social worker tries to do for the disease of the body politic what the physician does for physical disease – to diagnose it, to cure it if possible, at least to alleviate the suffering it causes…In some of the large provincial cities the local University already provides for the teaching of the doctor, lawyer, engineer, architect, even the dentist, farmer, and dyer: why not also of the social worker?

Elizabeth Macadam, 1914

Elizabeth Macadam, born this month in 1871 near Glasgow, became closely associated with Liverpool and its university through her activities in the field of social work. Records from two of the bodies she was involved in, the Victoria Settlement and the university’s own School of Social Science and of Training for Social Work, are held by Special Collections and Archives. Examination of this material reveals the establishment and early development of these bodies, as well as the personal roles played by Macadam and that of her close friend and colleague Eleanor Rathbone.

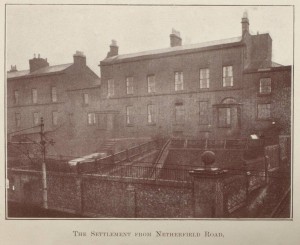

Before her move to Liverpool in 1902 Macadam had received a grounding in social work at the Women’s University Settlement in Southwark. It was the chance to run her own settlement which tempted her northwards. Liverpool’s Victoria Women’s Settlement, situated in Netherfield Road in the working class area of Everton, had been opened in 1898 under the auspices of the Liverpool Union of Women Workers, as a residential home for women engaged in social work. The aim, according to a booklet produced by the organisation in 1913 (D45/4/1), was ‘to bring the two social elements commonly designated as “rich” and “poor” into some sort of natural and friendly relations with each other, so that each might get to know and understand a little of the other.’ From the early days of the settlement, volunteers organised a dispensary for women and children, set up social clubs for girls, and arranged classes for invalid children. Macadam worked alongside other women prominent in the field of social work, including Eleanor Rathbone (who was Honorary Secretary of the settlement), Emily Oliver Jones, Lydia Booth, and Edith Bright. Under Macadam’s wardenship the settlement thrived, thanks in part to the increased emphasis she placed on the professionalization of social work and the need for formal training: the 1910 annual report stated that the settlement had

steadily grown in value and importance, not only because of its manifold practical activities, but also because it has become an acknowledged centre of information and a training ground for students in sociology. That it should have attained this position in so short a time is undoubtedly due to the practical wisdom, the organising ability, the unfailing tact, and the great personal charm of the Warden.

The training of the settlement’s workers was undertaken in association with the Liverpool University School of Social Science and of Training for Social Work, established in January 1905; Liverpool became the first British city after London to start a school of this kind in connection with its university. As well as workers from the settlement (twelve of the initial intake of students were from Netherfield Road), the school also played host to men and women engaged in various fields of work involving social service, including doctors, clergymen, Poor Law officials, teachers, trade union organisers, and matrons. Macadam and Rathbone served on the committee of the new school and both taught classes under its auspices, alongside staff from the University, including the historian Ramsey Muir and Professor of Political Economy E. K. Gonner. Lectures were given on various subjects, including civic administration, the poor law, history of local government, and social ethics. But the school also placed great emphasis on giving practical experience to its students, with most of this practical work being organised through the settlement: Macadam herself stated that ‘if anything must go, let it be lectures and books, not the opportunities of gaining experience and taking a personal share for a time in constructive schemes for social reform’ (see her article, The Universities and the Training of the Social Worker, 1914). Macadam dedicated more and more of her time to the school, resigning her wardenship of the Victoria Settlement in 1910 to focus on its activities, and in 1911 she was awarded a Lectureship in the Methods and Practice of Social Work. In 1917 the school became an official part of the University of Liverpool.

The activities of the School of Social Science and the Victoria Settlement were, unsurprisingly, influenced by the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, as revealed by the annual reports of both organisations. The settlement claimed in its 1915 report that ‘in making provision for the dependents of soldiers and sailors as well as, to a lesser degree, in the relief of distress among the civilian population, the Settlement has taken a very active and prominent part.’ Neither was the School of Social Science idle in terms of the services offered to aid the war effort. Lectures and full courses were given on relevant subjects for students and/or the public, such as methods of assistance to families of those serving in the armed forces, war economy, and welfare work in factories. The importance of having individuals trained in social work was made clear during the war, with the settlement claiming that

the war has proved beyond doubt that that it is trained workers who are needed, women who have been taught to organise and to work on modern scientific lines, and not the well-meaning amateur who has time to give but lacks the training that would make time of great value.

Macadam herself served the war effort in numerous ways. From 1916 she was granted a leave of absence from the university to assist in the setting up training programmes for welfare workers in factories on behalf of the Ministry of Munitions. In 1919 she left Liverpool permanently for London to become secretary of the newly established Joint University Council for Social Studies. Both the Victoria Settlement and the School of Social Science continued. In 1928 the first student to take an Honours Degree in Social Science graduated; this was Margaret Simey, who also volunteered at the settlement. Simey would go on to play an active role in local politics and voluntary services. The school became the university’s Department of Sociology in 1971.