On Sunday 08th of May 1949, the singer and political activist, Paul Robeson gave a concert and talk at St George’s Hall in Liverpool. An open-air concert given by Robeson earlier in the day attracted 2000 people and a dozen officials ‘struggled to clear a path’ for the singer as he left. The evening talk was chaired by the Merseyside author and peace campaigner Olaf Stapledon.

The concert marks a fascinating meeting of two public figures at key moments in each of their lives and gives us a glimpse of the political response to racism in Liverpool at the cusp of the 1950s. For Black History Month, we take a look at the archives of Stapledon held at the University of Liverpool to find out a little more about this event and what it can tell us about the history of anti-racism in the city.

By 1949 Robeson was a well-known public figure. He had risen to prominence through a successful career as a singer and actor before entering into politics where he campaigned for leftist causes and the end to racial oppression for African Americans. In February 1949 Robeson began a four-month tour of Europe to draw attention to racial oppression. The format of giving a concert alongside a talk drew huge crowds and allowed him to spread his message to those interested mainly in his music.

In April 1949 he spoke at The Congress of the World Peace Partisans in Paris, an international world peace conference. His mis-reported comments concerning the right of African Americans to refuse to fight for the U.S. caused almost universal outrage back home and would lead to an increasingly hostile reception for him in America. The comments, though, did nothing to diminish his warm reception in Europe where generally his concerts were sold out. Robeson heard of the negative press in early May, a week or so before his concert in Liverpool, writing to a friend in his short-hand style ‘Distorted—but let it rest.’

Stapledon himself was at the centre of media attention for similar reasons in 1949. A philosopher by training, Stapledon had written visionary science fiction novels in the 1930s (Last and First Men (1930) and Star Maker (1937)), before, like Robeson, turning to anti-fascist campaigning in the late 1930s. In the immediate post-war era, Stapledon accepted invitations to a number of world peace conferences. In late March 1949, Stapledon attended The Cultural and Scientific Congress for World Peace. In order to isolate the conference organisers, U.S. government officials rescinded all visas for Western European delegates except for Stapledon. As the only delegate from Western Europe, Stapledon was catapulted into the limelight, speaking at press conferences, giving multiple addresses and even taking part in a live televised debate with the philosopher Sidney Hook.

Robeson and Stapledon had only met once before the meeting in Liverpool and then only the month before at the Paris peace conference. Stapledon, though, had been a fan of Robeson for a number of years. He collected Robeson records from the late 1920s and had seen him perform Othello in London in 1930.

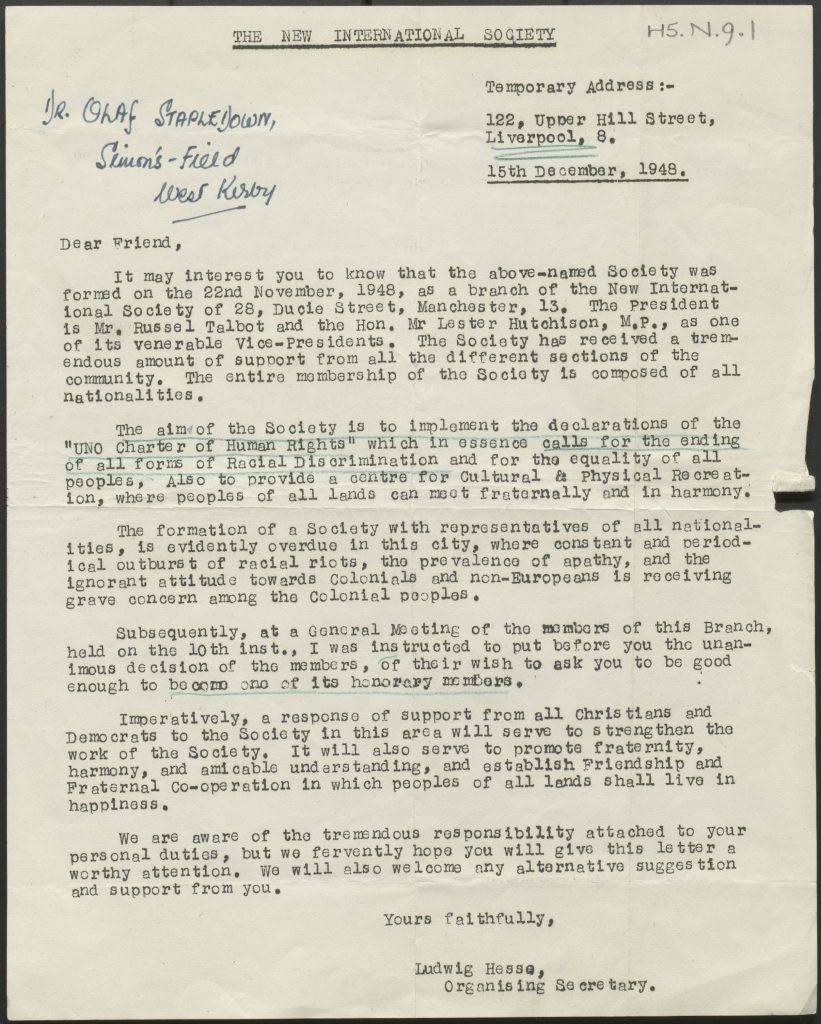

Stapledon was first approached by the group that organised the Liverpool concert, the Liverpool branch of the New International Society, to be an honorary member in late 1948. The letter from Ludwig Hesse is dated 15th December 1948 and outlines the aims and context of the New International Society (figure 1). Hesse states that the aims of the society were to implement the UNO charter of Human Rights ‘which in essence calls for the ending of all forms of Racial Discrimination.’ Hesse goes on to say that the society is ‘evidently overdue in this city where, constant and periodical outburst of racial riots, the prevalence of apathy, and the ignorant attitude towards colonials and non-Europeans is causing grave concern among the colonial peoples.’

Figure 1. Letter from Ludwig Hesse to Olaf Stapledon, 15th December 1948. OS/H5/N9/1.

Hesse refers to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that had passed merely days earlier on the 10th December, which called for freedom and equality of all people regardless of a number of characteristics including race. Stapledon, clearly taken by the society, had underlined this section in green pencil. Hesse’s reference to ‘constant and periodical outbursts of racial riots’ is most likely in the first instance to the racist riots that broke out in Liverpool a few months earlier in August 1948, where white rioters attacked businesses that catered to the Black inhabitants of Liverpool. Hesse gives the sense of city both physically and socially hostile to the people of colour living in the city.

On Stapledon’s return from the New York peace conference he received a further letter from Hesse. The letter ostensibly advertises Robeson’s visit to Liverpool without yet inviting Stapledon to chair the meeting. Hesse writes of the ‘admiration you earned throughout the world by the fortitude you maintained in defence of Democracy and World Peace’ in reference to the prominent part he played in the peace conference in New York.

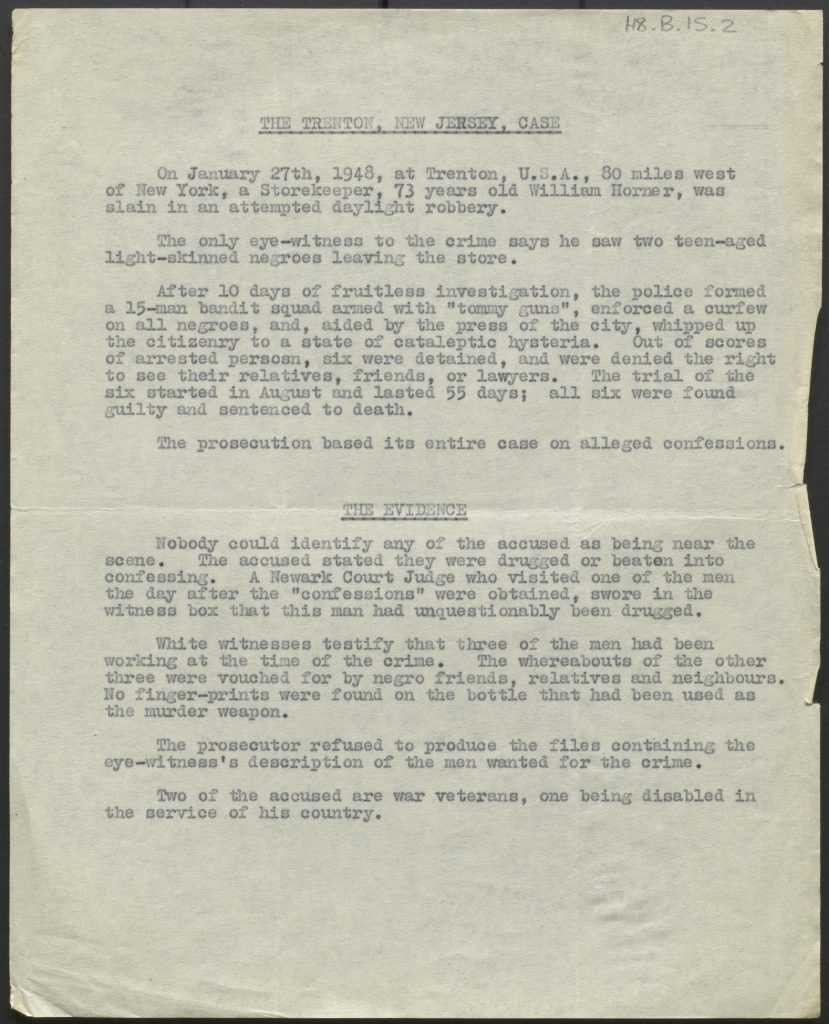

Subsequent letters from the NIS are addressed from Joan Frood and relate directly to the organisation of the Robeson concert. On the 13th of April, Frood writes to ask Stapledon to chair the meeting and mentions the inclusion of a document about the topic of conversation, ‘the Trenton case’, that Robeson wanted to discuss. The document was retained by Stapledon and is now part of the Stapledon archive (see figure 2 [OS/H8/B15/2). The Trenton case concerned a U.S. legal case in which six African Americans had been sentenced to death for murder by an all-white jury on dubious evidence. She also expresses ‘the great difficulty in securing a large hall.’

Figure 2. Document summarising The Trenton Six case in Stapledon’s papers. OS/H8/B15/2

A letter dated 2nd of May mentions again ‘innumerable hitches regarding the Hall’. Frood explains that the NIS were told that St George’s Hall could not be used due to the delayed installation of new seating. However, she suspects that ‘seating is not the real obstacle.’ Frood does not elaborate so it is not possible to say with certainty why the Hall did not want to host Robeson. However, due to the nature of Robeson’s public profile and the aims and membership of the NIS, it is a fair guess that racism played a part.

The final letter from the NIS dated 11th May indicates that the concert went ahead and was a success. Frood reports that all ‘praised your speech and your tactful handling of such a crowded meeting’ and apologises for not having thanked Stapledon in person due to the ‘upheaval’ that followed the meeting. Again, Frood does not elaborate, but the reports of huge crowds at the earlier open-air concert and the reference to the crowded nature of the meeting suggests that the upheaval was due to the large number of people in attendance.

Frood’s letter was the last from the NIS and, as far as we know, the meeting was the last contact between Stapledon and Robeson. Robeson would return to the US on the 16th June after a further tour of Eastern-Europe and Russia. In the ensuing decade, Robeson found himself constantly under attack by regressive and racist forces in the U.S. In August, Robeson would be at the centre of the Peekskill riots in which racist townspeople attacked attendees on their way to a Robeson concert in Peekskill, New York. In the early 1950s, Robeson’s passport was withdrawn by the State Department and only returned in 1958. Finally, in 1956, Robeson was called before the House of Un-American Activities Committee and grilled about his political sympathies. The 1960s saw his health deteriorate and he died in 1976.

Stapledon would be dead within a year and a half of the Robeson concert. In this short time, he turned his attention to anti-colonialism and civil rights. In 1950 he joined the nascent anti-apartheid campaign against the white supremacist government in South Africa.

The letters from Hesse and Frood to Stapledon give us a snapshot of the campaign for racial equality in Liverpool in the late 1940s. We can see how campaigners viewed the issue as both a national and international affair, taking in tensions in Liverpool and the US and harnessing the fame of Robeson to further the aims of the NIS. They also give a sense of the joy and welcome given to Robeson at a time of heightened hostility to him at home. Finally, the meeting between Stapledon and Robeson quite possibly affected the final year or so of Stapledon’s life directing him toward anti-racism and anti-imperialism.

These letters form a part of the larger Stapledon archive held at the University of Liverpool. If you are interested in the NIS letters or Stapledon’s life and career, you can view the catalogue here: Context: OS – The Manuscripts, Correspondence and Books of Olaf Stapledon

Works referenced:

Crossley, Robert, Olaf Stapledon, Speaking for the Future (Liverpool : Liverpool University Press, 1994).

Duberman, Martin Bauml , Paul Robeson: A Biography (New York : Ballantine Books, 1989).

Murphy, Andrea, From the Empire to the Rialto: Racism and Reaction in Liverpool 1918-1948 (Rock Ferry : Liver Press, 1995).

Liverpool Evening Express 09 May 1949

My special thanks to Janaya Pickett for providing research and advice.