The Digital Heritage Lab’s Voyager at 50 is a celebration of the Voyager 1 and 2 probes, which were sent into space in 1977 with golden records containing information about humanity in case the probes should be found by alien intelligences after leaving the solar system. The exhibition uses items from the University of Liverpool’s Science Fiction Collections to reflect on how humans have imagined alien communication, the difficulties we may encounter, and the possible solutions we have thought of. One of the items chosen is the manuscript for Ian Watson’s novel The Embedding.

That The Embedding (1973, Gollancz) was Ian Watson’s debut novel speaks to his remarkable intellect and literary ambition. The novel is a complex work that engages with linguistics as seriously and as rigorously as any hard science fiction novel does with physics. Watson interweaves three narrative threads, one about a Brazilian tribe whose language alters the perception of those who use it, one following deeply unethical linguistic and perceptual experiments on children to expand the capacity of the human brain, and one following a spaceship heading towards Earth bringing with it humanity’s first contact with an alien race. Watson’s archives are housed in Science Fiction Collections held at the University of Liverpool’s Special Collections and Archives department. One of the items in the archive is the original manuscript for The Embedding. The box folder contains both the e manuscript, in this case the final version sent to the publisher for typesetting and printing, and the d manuscript, the version before this. The d manuscript is particularly interesting, because it shows the extent to which Watson was editing and rewriting even at this late stage. Items like this demonstrate the kind of insights the archive can offer into the study of science fiction.

The Embedding has a number of linguistic concepts at its core. One such concept is the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, that the concepts a language has words for shapes how users perceive the world. The scientists at the Haddon Neurotherapy Unit have come up with a novel way of testing the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, by raising children isolated in artificially designed environments and seeing how the languages they develop to cope with these environments shape their brain development. Another key linguistic concept is the idea of self-embedding, which gives the novel its name. This refers to the amount of information that can be recursively embedded within a sentence before the sentence becomes impossible to understand. The linguists are trying to force increased cranial capacity on the child subjects of their experiments by increasing the levels of embedding within the languages, thus increasing the amount of information a person can sort through and make sense of in their short-term memory. A third is Noam Chomsky’s idea that the plan for learning human languages is programmed into the brain at birth. The linguists hope to reverse-engineer all possible human languages through creating conditions for all these different languages to arise, and so recover languages that have been lost or forgotten. Thus Watson’s novel becomes a laboratory for investigating thought experiments in which linguistics are the science under investigation.

In order to successfully do this, Watson’s novel must explain these complex linguistic ideas to an audience largely unfamiliar with them, in a way that is clearly understandable and interesting. Part of what makes this manuscript so fascinating is that the reader can see how many of these late period edits centre around how the book explains these linguistic ideas. Watson realizes that The Embedding will sink or swim depending on how well it can get across these ideas, many of which will not be intuitive to the average science fiction reader who, in the 1970s at least, one could probably assume would be much more familiar with physics and engineering than linguistics and the social sciences.

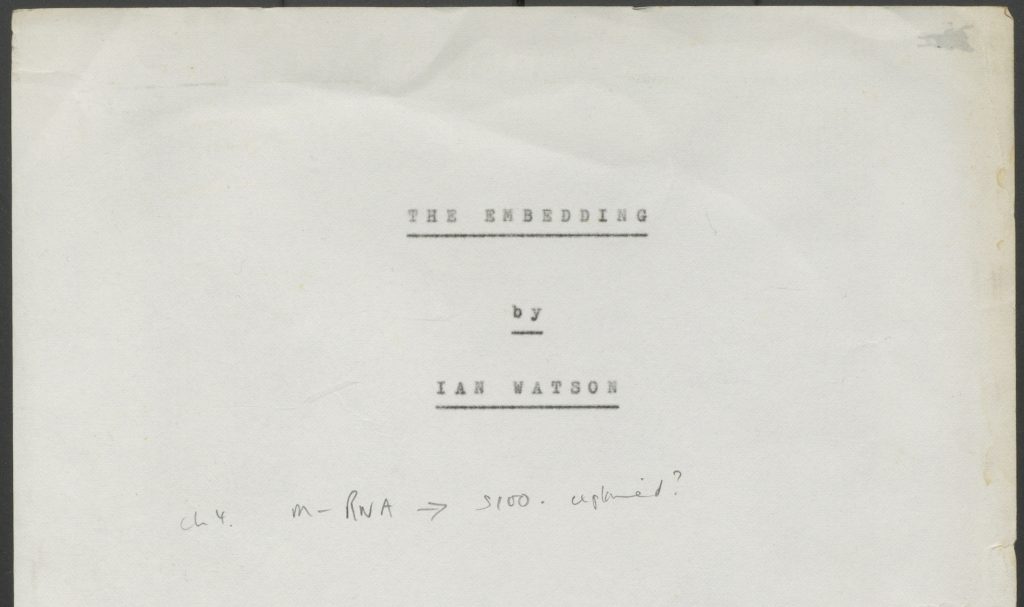

Front page of Manuscript d of The Embedding by Ian Watson from the Ian Watson archive at the University of Liverpool (uncatalogued).

On the title page, Watson has made a note to himself about chapter four, where he explains the mechanisms of language and memory, to check his explanation of the role that mRNA plays in the formation of memory. Looking at chapter four, one of the many parts of the book in which characters have in-depth conversations about linguistics and the theories Watson is exploring in the novel, one can see many of these passages being rewritten, edited and added to, even at this late stage in the manuscript. This gives us an indication of how seriously Watson takes the science of linguistics, and the care with which he worked on the explanations in his novel to make them both engaging and understandable.

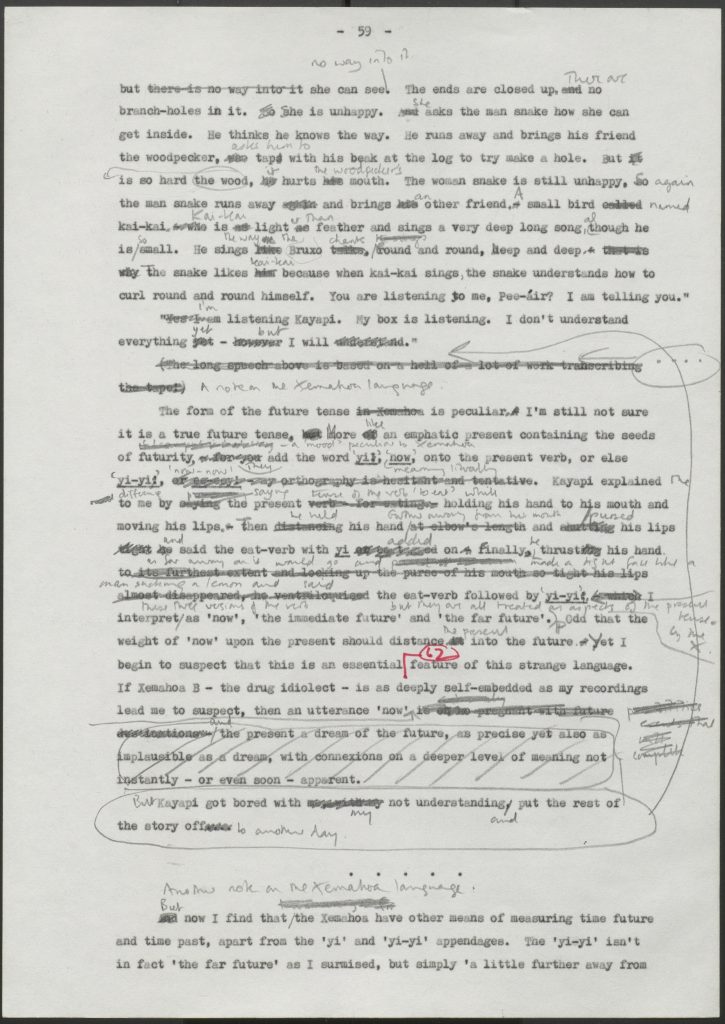

Page 59 and opposite blank page of Manuscript d of The Embedding by Ian Watson from the Ian Watson archive at the University of Liverpool (uncatalogued).

We can see an interesting example of this on page 59 of the manuscript. This section is from the perspective of Pierre, a linguist and anthropologist working with the Brazilian Xemahoa tribe trying to understand their language. Here he describes how the two forms of the language, Xemahoa A which is spoken everyday by the tribe, and Xemahoa B, the deeply embedded language which can only be accessed through ritualistic drug use, deal with the present tense. We can see that originally, Watson has written:

If Xemahoa B – the drug idiolect – is as deeply self-embedded as my recordings lead me to suspect, then an utterance ‘now’ is oh so pregnant with future destinations – the present a dream of the future, as precise yet also as implausible as a dream, with connexions [sic] on a deeper level of meaning not instantly – or even soon – apparent. [The Embedding manuscript d, 59]

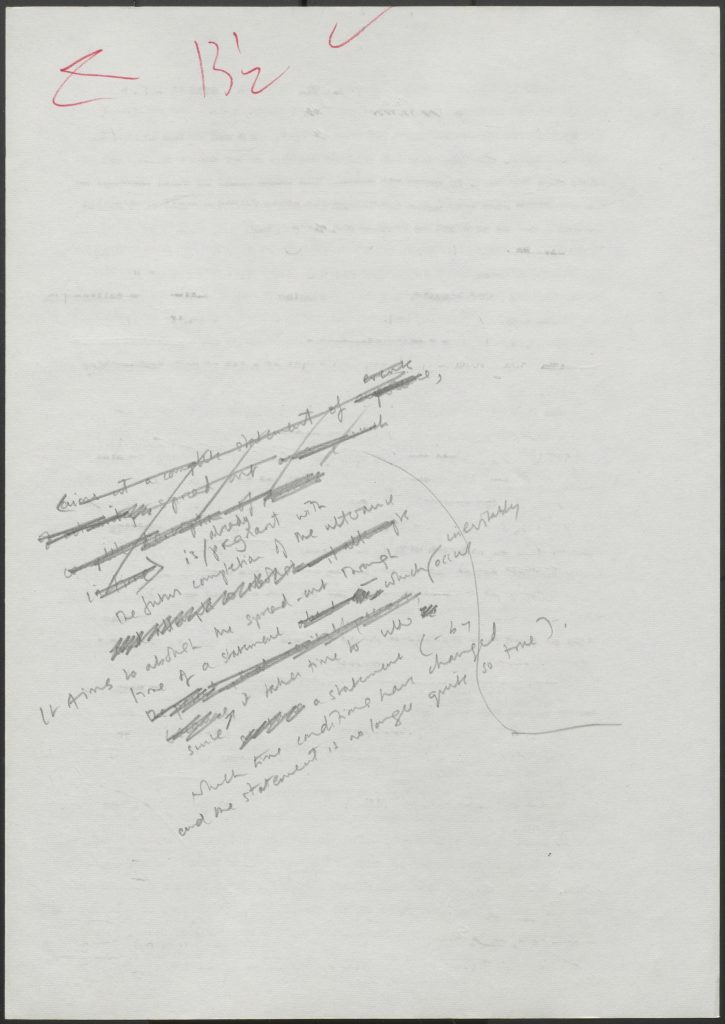

This has been crossed out, and Watson has handwritten on the opposing page the rewritten section, as it appears in the final published novel:

… then an utterance ‘now’ is already pregnant with the future completion of the utterance. It aims to abolish the spreadout through time of a statement – which inevitably occurs since it takes time to utter a statement (by which time conditions have changed and the statement may no longer be true). [The Embedding 1980 Granada, 50]

Watson’s rewriting makes the passage more direct – the language concerns itself not with future “destinations” but “completion”, implying a single chosen outcome rather than a multiplicity of possibilities. Similarly, instead of conceiving of the present as “a dream of the future”, with all the ambiguity that entails, Watson emphasizes how the language “aims to abolish the spreadout through time of a statement”. It changes the passage’s emphasis to one chosen outcome of the future, rather than a range of vague potentials. This helps to underline how the languages’ different approach to tenses implies a very different perception and understanding of time, highlighting the novel’s theme of the ways in which language shapes how we experience reality. The novel’s in-depth imaginings of how linguistics can shape thought highlights one of the many unusual problems that aliens encountering the Voyager probes may face when they try to understand the information we have sent them in the golden records. See more about the exhibition at the link: https://digitalheritagelab.liverpool.ac.uk/voyager

Text written by Jonathan Thornton.

Permission to reproduce images from The Embedding Manuscript d kindly given by Ian Watson.