SC&A was recently able to acquire some 22 items printed or published in Liverpool during the late eighteen or early nineteenth centuries, to add to its already extensive collections of local history, literature and publishing. Several items were displayed in Manuscripts and More on 17 August. Among the rest of the recent acquisitions are several in verse. 150 years before The Mersey Sound, Liverpool already had a busy community of poets such as Sarah Medley, whose book of Original poems: sacred and miscellaneous (1807; SPEC 2017.a.019) was printed here by James Smith; Robert Merdant, author of Country people; or, Pastoral poetry (1810), printed locally by Thomas Kaye (1810; SPEC 2017.a.008), and T. G. Lace, whose Ode on the present state of Europe was printed by M. Galway & Co in 1811, during the Napoleonic wars (SPEC 2016.PF1.14).

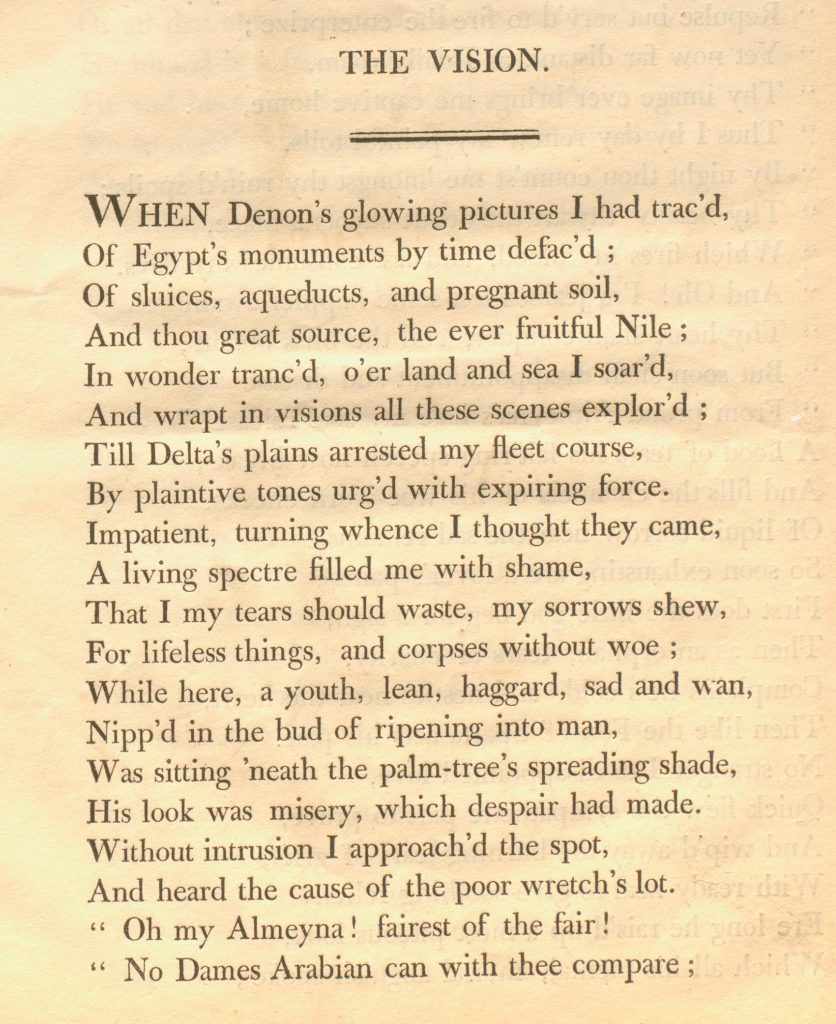

The vision for coquettes. An Arabian tale (SPEC 2017.c.006) a poem of unknown authorship, was printed by John M’Creery in 1804 and sold by, among others, the well-known Liverpool poet, abolitionist and bookseller Edward Rushton from his shop in Paradise Street.

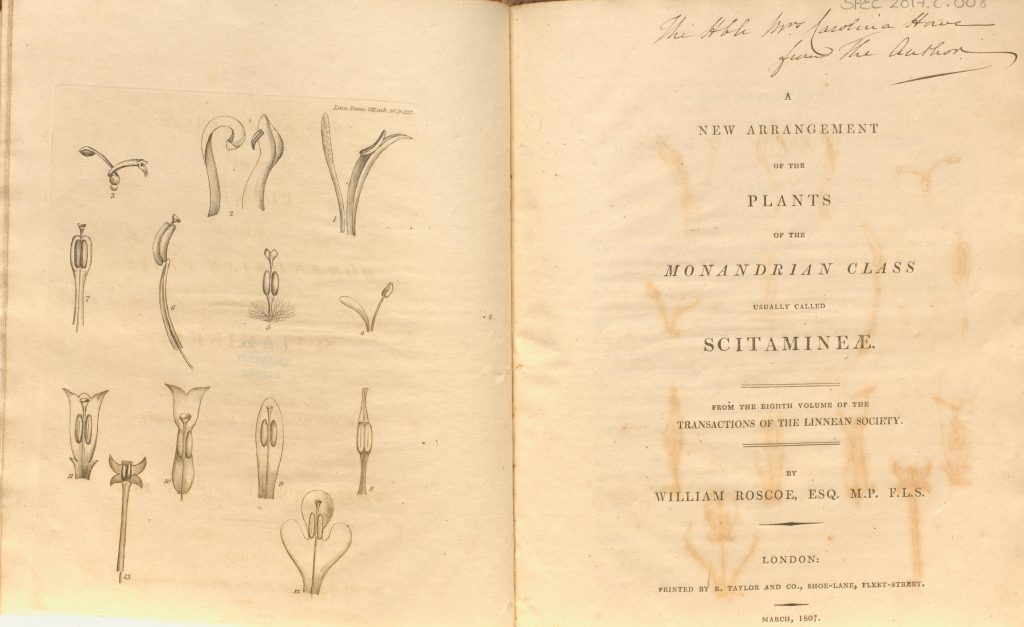

Several of the new items feature William Roscoe (1753-1851), the most prominent member of Liverpool’s intellectual community at this date and its most prolific author. These new items include several political pamphlets and one of his scientific works, A new arrangement of the plants of the monandrian class usually called scitamineae, published in London during Roscoe’s brief career as MP for Liverpool (1807; SPEC 2017.c.008).

SC&A also now hold one of the few copies in the UK of his anti-slavery campaign poem, The wrongs of Africa (in two parts: London 1787-8; SPEC 2017.b.011). Roscoe’s writing career had started with an Ode, printed in a few copies in 1774, which was then added to a meditative verse account of the area he was brought up in: Mount Pleasant: A descriptive poem which was printed at Warrington in 1777 (SPEC G11A(32.5)). The wrongs of Africa was his next poem, and marked a complete change of direction, inaugurating as it did the work of a circle of abolitionist poets living and working in Liverpool. These included Rushton, whose West-Indian eclogues appeared later in 1787 (in London); the Irish émigré engraver Hugh Mulligan, author of Poems chiefly on slavery and oppression (London, 1788), Peter Newby’s The wrongs of Almoona (printed by H. Hodgson in Liverpool, 1788), and Thomas Hall’s Achmet to Selim, or, The dying negro (printed in Liverpool by M’Creery in 1792). Part one of Roscoe’s poem was published in May 1787 and part two in February 1788; it was republished in Philadelphia later that year. More copies of the Liverpool printing survive in America than do in Britain; ours is one of eight copies known in UK libraries. It was formerly in Worcester Public Library.

Roscoe’s poem was published in an era when writing by slaves was, for obvious reasons, hardly known at all. Letters of the late Ignatius Sancho, an African, had appeared in 1782, and The interesting narrative of the life of Olaudah Equiano, one of the earliest formal autobiographies by a former slave, came out in 1789. Meanwhile abolition-minded writers in Liverpool and Bristol supplied the deficiency through the medium of poetic scenes and narratives in which slaves, normally denied a voice, were imagined to state their feelings to a sympathetic readership. The point was to engage public feeling by focusing on realities of life on the plantations and the suffering of the enslaved Africans. Roscoe complemented his verse tale with a soberly-argued prose account, A general view of the African slave-trade, demonstrating its injustice and impolicy: with hints towards a bill for its abolition (1788).

The poem is more psychological and emotive than economic or political in focus. According to the ‘Advertisement’ to the Part Two, it was originally planned in three parts, to focus sequentially on Africa, the passage to America, and the colonies, but only two parts were completed. Part One asks readers to transform the ‘sensibility’ they bring to the reading of sentimental fiction to active human sympathy in a pressingly real situation. It also addresses slave masters and the captains of slaving ships and a local ‘veteran trafficker’, in an attempt to provoke examination of the strange and twisted psychology involved in the enslavement of other human beings. It takes readers on an imaginary journey to Angola, portrays the peaceful life of the inhabitants before traders arrive, and blames the traders for corrupting local customs and covering the continent with fear. An inset story of two brothers, Arebo and Corymbo, caught up in a devastating raid, gives the narrative direct human appeal. Part Two imagines the passage to America from the perspective of the captured Africans. A planned revolt is bloodily thwarted. Its leader, Cymbello, an African prince educated in political principles similar to Roscoe’s own, and partly formed on the model of Aphra Behn’s seventeenth-century ‘royal slave’ Oroonoko, dies courageously with his lover in the carnage. The last pages of the poem are devoted to a wide-ranging history of the concept of Freedom and a final address from Freedom herself, prophesying her final victory over the tyrants and enslavers of Europe and the world.

A year after Part Two was published, the French Revolution appeared to begin to dismantle the institutions of oppression (as they were perceived by Roscoe and his political allies). It would be another twenty years before the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act finally passed the House of Commons, and decades more before the practice itself was outlawed; but poems like Roscoe’s were an important initial element in the campaign, defiantly continued by Roscoe and his colleagues in Liverpool, Bristol and London, to bring the atrocities of the trade to public view and to stimulate human sympathy for an otherwise largely voiceless and invisible mass of people. It is fitting that this rare printed item should return to the place where it was written.

A guest blog post written by Paul Baines from the Department of English.