From Victor Frankenstein bringing his monster to life in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) to people grown in pods in The Matrix (1999), science fiction has long imagined the process of creating life outside the human body.

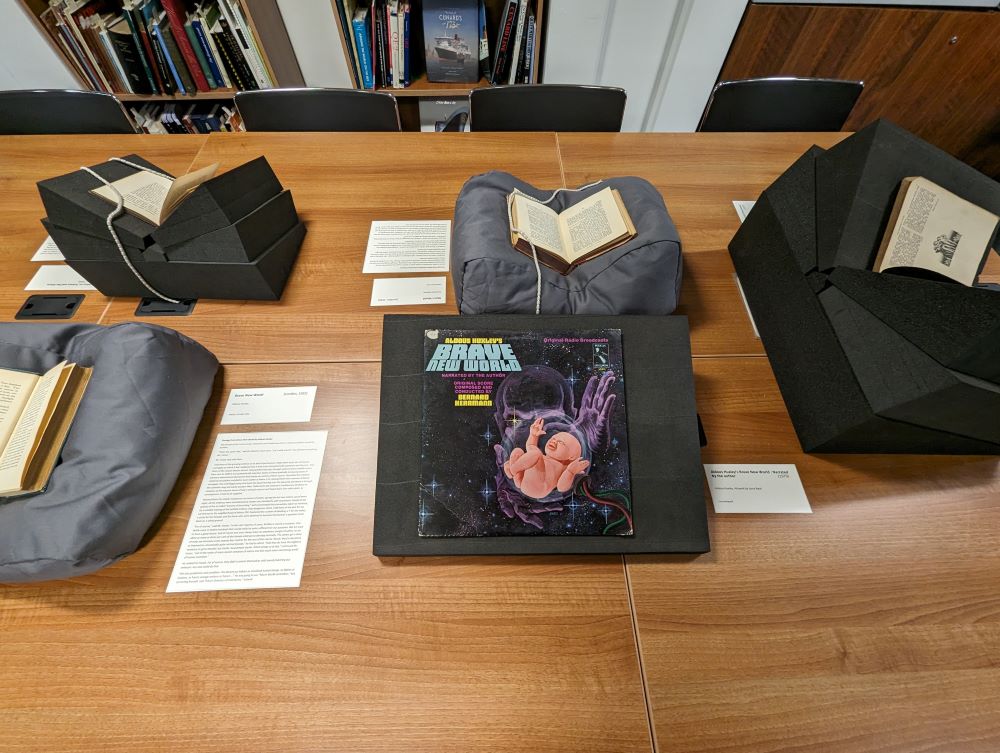

On Wednesday the 10th of April we hosted an event at the Special Collections and Archives department on the topic of science fiction and ectogenesis—the science of growing organisms outside of a biological body. The event was part of a conference taking place at the University of Liverpool on the 10th and 11th of April titled ‘Normative Implications of the Metaphysics of Extra-Corporeal Gestation’. The conference aimed to think through the philosophical and ethical implications of ectogenesis and is part of a larger project The Future of Reproduction supported by the Welcome Trust.

Though the speakers and participants at the conference mostly worked in the fields of philosophy, law, and bio-ethics, the images most closely associated with ectogenesis in the popular imagination derive from fiction. The organisers therefore asked that we put on a display of items relating to ectogenesis alongside a talk given by Dr Anna McFarlane (University of Leeds) on ectogenesis in science fiction.

McFarlane began by outlining why science fiction can be a useful tool for thinking about the present and the future. It can function either to describe the world as it is now or to speculate about future scientific developments and their impact on society. McFarlane then gave an outline of the representations of ectogenesis in science fiction, beginning with its problematic genesis in the eugenics movement in Britain in the interwar period to its ambivalent depiction in feminist texts in the 1960s and 1970s. She ended with reflections on contemporary novels that explore artificial wombs many of which reflect increasing anxiety over the commodification of medicine in the twenty-first century. The talk was a generous overview both for those science fiction readers unaware of ectogenesis and for philosophers and legal scholars of ectogenesis who knew less about the role it has played in science fiction. It also contained some interesting readings of well-known texts such as Brave New World (1932) and lesser-known contemporary works such as Baby X (2016).

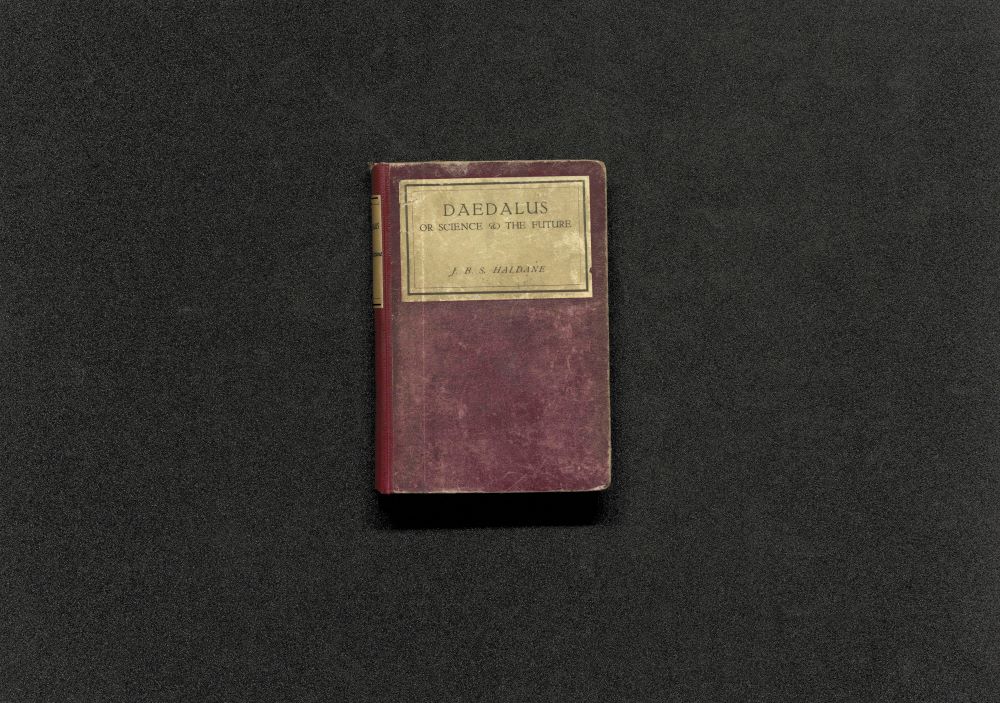

The display contained many of the texts explored in McFarlane’s talk. For instance, one of the items was a first edition of J. B. S. Haldane’s speculative scientific book Daedalus: or, Science and the Future (1924). Haldane coined the term ectogenesis in the book in a section written in the voice of a future undergraduate student looking back on developments in biological sciences in the twentieth century. The genesis of ectogenesis then is one rooted in the techniques of science fiction.

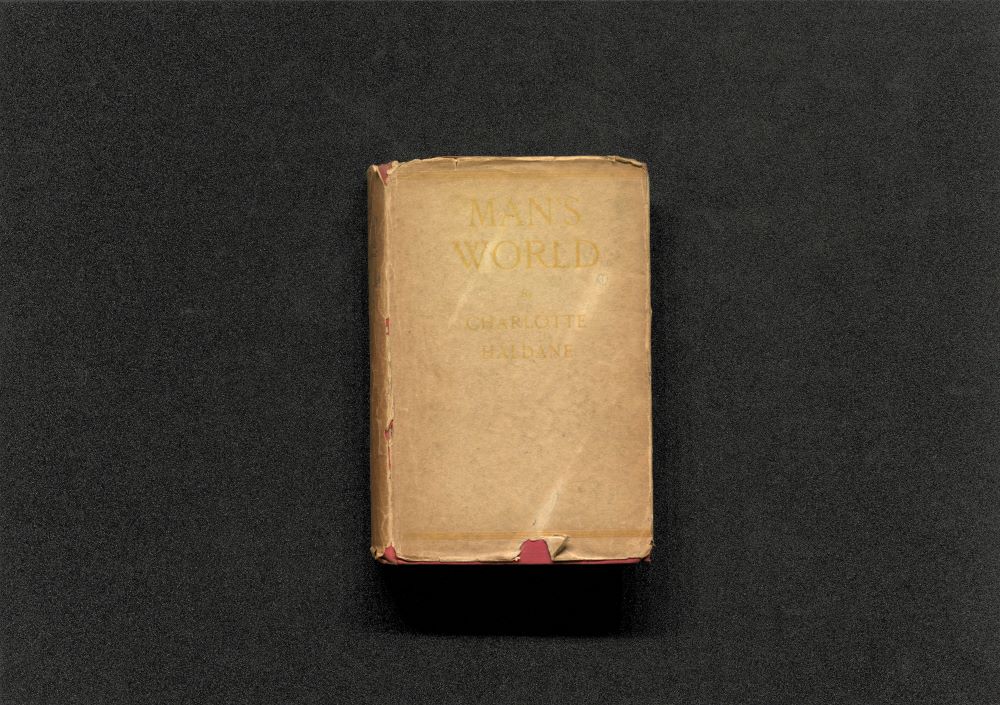

One of the first fictional accounts of ectogenesis was Man’s World by Charlotte Haldane, who herself was married to J. B. S. Haldane. The book is a dystopia set in a white supremacist world state in which a eugenics programme selects women for motherhood. Though ectogenesis is not fully realised for human use in the book, characters chillingly speculate about its potential for eugenics. The first edition copy on display is inscribed by Arthur C. Clarke, the science fiction author best known for his collaboration with Stanley Kubrick on 2001: A Space Odyssey.

As well as showing some of the original texts to explore ectogenesis, we also had some items on display from the period of second wave feminism that explored the concept often with a certain ambivalence. One such text was ‘Dr. Gelabius’ (1968), a short story by Hilary Bailey first published in New Worlds magazine in 1968. The story describes the nefarious Dr Gelabius going about his eugenics work in his laboratory filled with foetuses in glass jars. The story is not well known today but was included in the influential anthology England Swings SF in 1968.

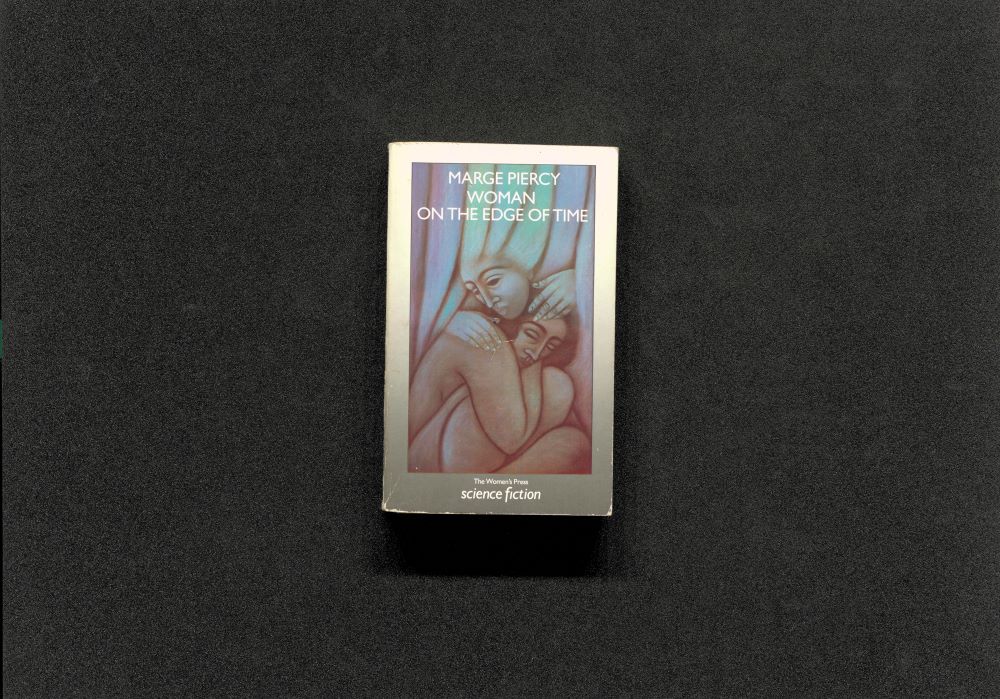

A better-known work that includes a rather more positive vision of ectogenesis is Woman on the Edge of Time (1976). The novel imagines a future utopia in which gestation takes place in a purpose-built structure, a brooder, where foetuses are grown in tanks. The protagonist, Consuelo Ramos, is disturbed but the inhabitants of the utopia defend the practice which they argue has a number of advantages for them: it avoids the dangers of childbirth, breaks down the primacy of genetic bonds, and allows the sexes to share childcare more equally. The copy on display was the Women’s Press edition from 1987 with cover art by Phyllis Mahon.

As McFarlane pointed out in her talk, representations of ectogenesis in science fiction have continued up to the present. The most recent item on display was the novel The Ten Percent Thief (2023) by Lavanya Lakshminarayan. The novel is set in a future Bangalore in which society is divided by a bell curve depending on the individual’s conformity to social norms. Natural birth is no longer encouraged due to the expense of maternity leave. Instead, most children are born via extra-corporal machines called ‘Pregapods’ so that women can continue working without monetary loss for corporations.

With ectogenesis soon to be a reality, its exploration in science fiction is set to continue. Though arguably images of ectogenesis in the genre have complicated discussions around ethics of the emergent technologies, science fiction will remain a powerful tool for narrativising ethical and legal issues. We ended the workshop by getting participants to write their own science fiction short stories. Those that we had time to listen to before the session ended engaged in various topics including genetic engineering, pregnancy, and gender relations. Not only did the stories show the usefulness of narrative for exploring ethical issues but were also of a high quality—an impressive feat given that the participants had such a short time in which to write them.