This year marks the 125th anniversary of Liverpool University Press. It is fitting, then, that we have recently acquired a copy of one of the first works to be published at the University Press at Liverpool (as it was then known). Social dreams: being an address given to the medical students of University College Liverpool (SPEC 2024.b.012), by Samuel Ashton Thompson Yates (1843-1903) was printed during the inaugural year of the press, on quality handmade paper, in a very short run of just 20 copies. It is a very elegantly produced little publication:

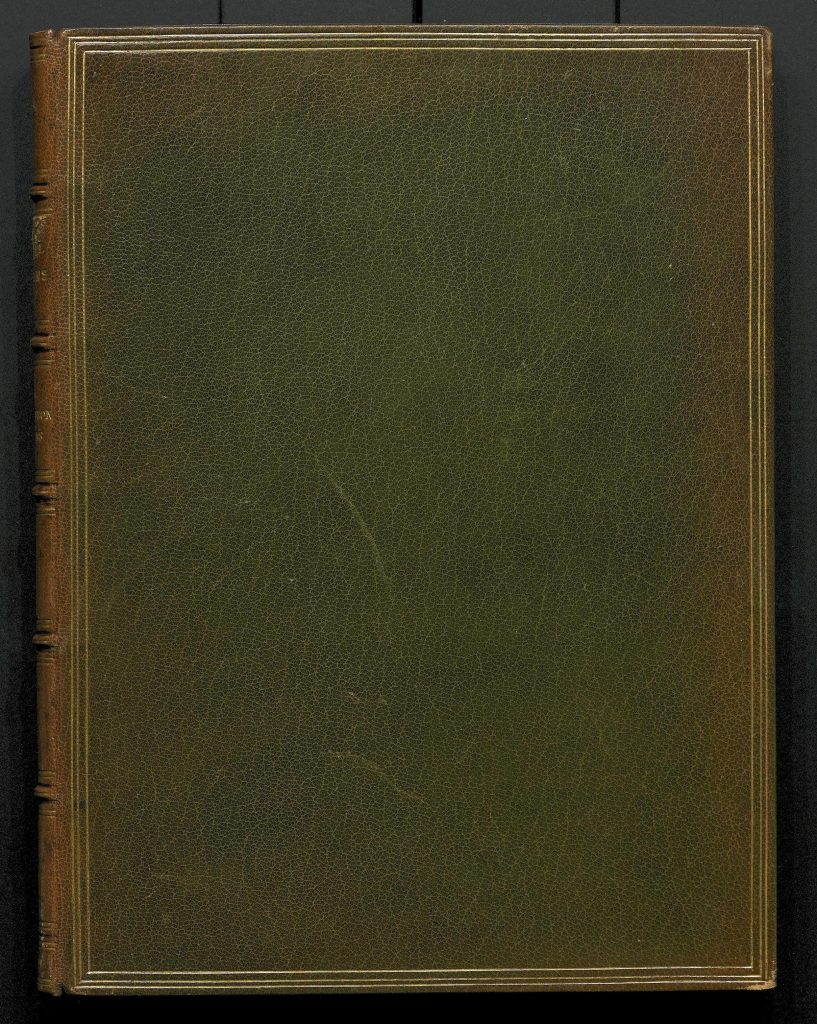

This particular copy of Social Dreams is from the library of its author. Like many of the books owned by the Reverend Samuel Ashton Thompson Yates it has had its elegance further enhanced by a fine binding of gilt tooled green goatskin, with gilded bookblock edges and brightly marbled endpapers, by the celebrated London bookbinder Roger de Coverly (1831-1914).

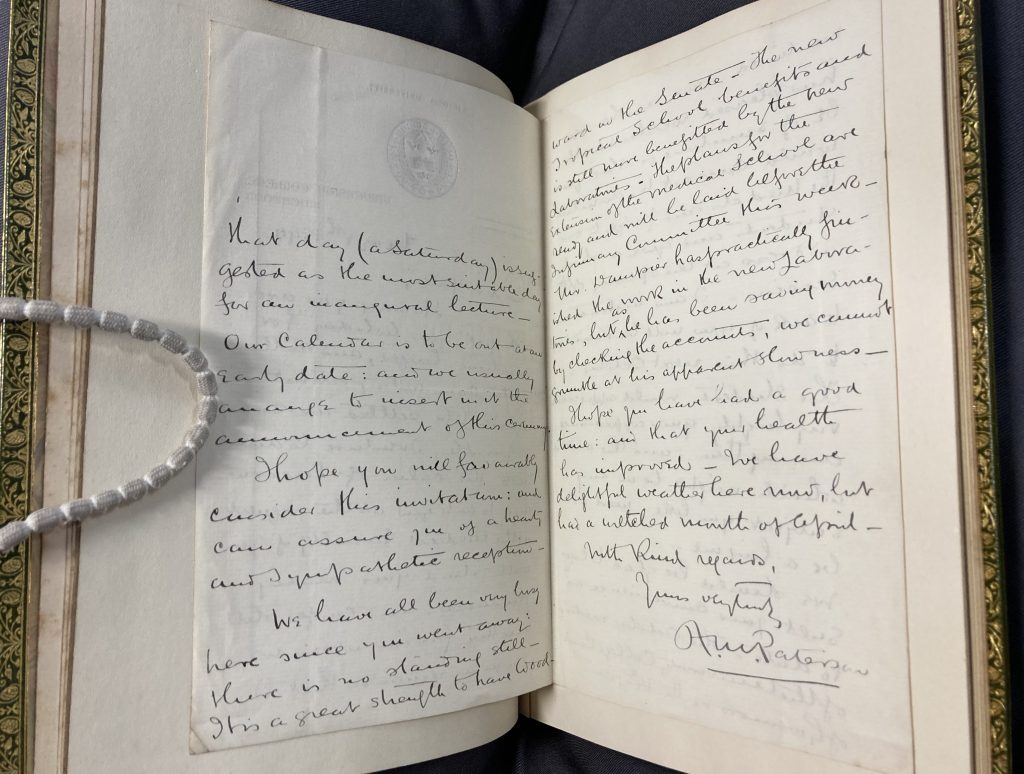

Also in common with many of the books in Thompson Yates’s library, during the rebinding a large number of blank leaves have been added at the front and rear of the book, and its owner has used these leaves to store articles and correspondence relating to his speech.

Thompson Yates had no medical background, rather this speech came about as a consequence of his philanthropic and charitable work – he gave several donations to Health Sciences at the University of Liverpool, and the 17 books from Samuel Ashton Thompson Yates’s collection recently acquired by Special Collections and Archives include both works by and correspondence with the celebrated professor of physiology, Charles Scott Sherrington (1857-1952).

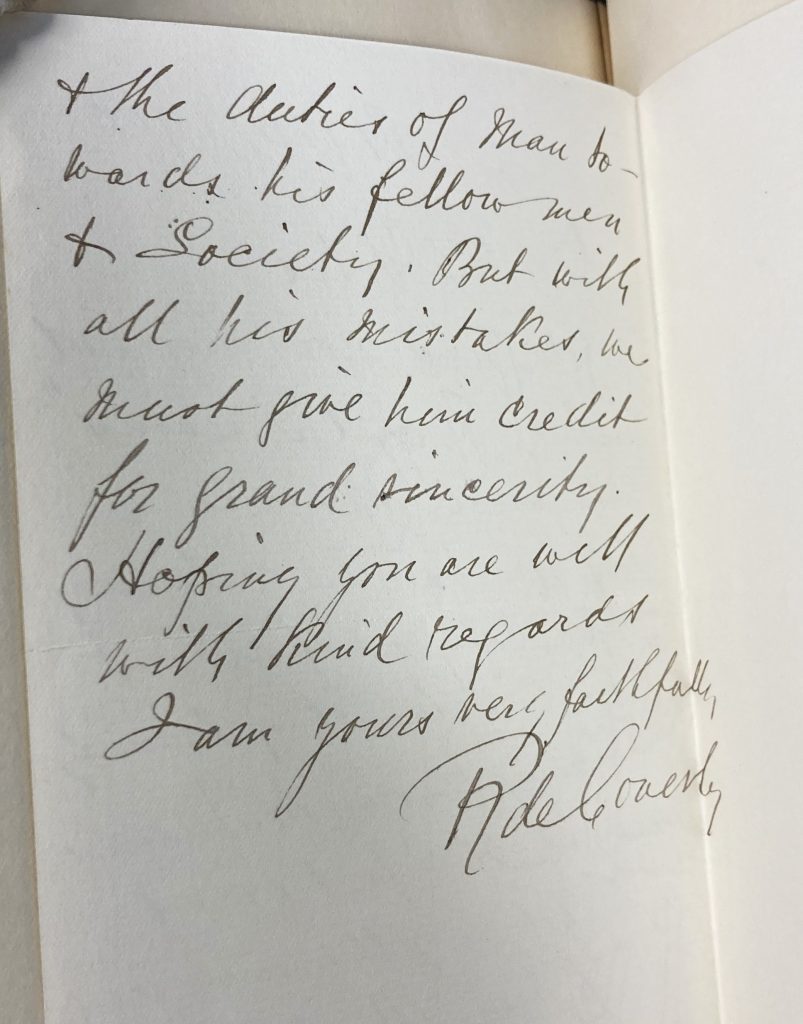

Thompson Yates’ speech does not concern medical matters then, but rather he takes as a starting point his recent reading of a biography of the author, artist and socialist activist William Morris (1834-1896). He praises Morris the artist and poet, “who has done much to educate the eye and the taste and to make life brighter and more beautiful for us all”. In this vein, he encourages the medical students that make up his audience not to confine themselves to their textbooks and empirical investigations, but to learn also from poetry, philosophy, history and literature. He sees less to admire, however, in Morris’s socialist politics, and advocates instead for the importance of individual responsibility and free-thinking.

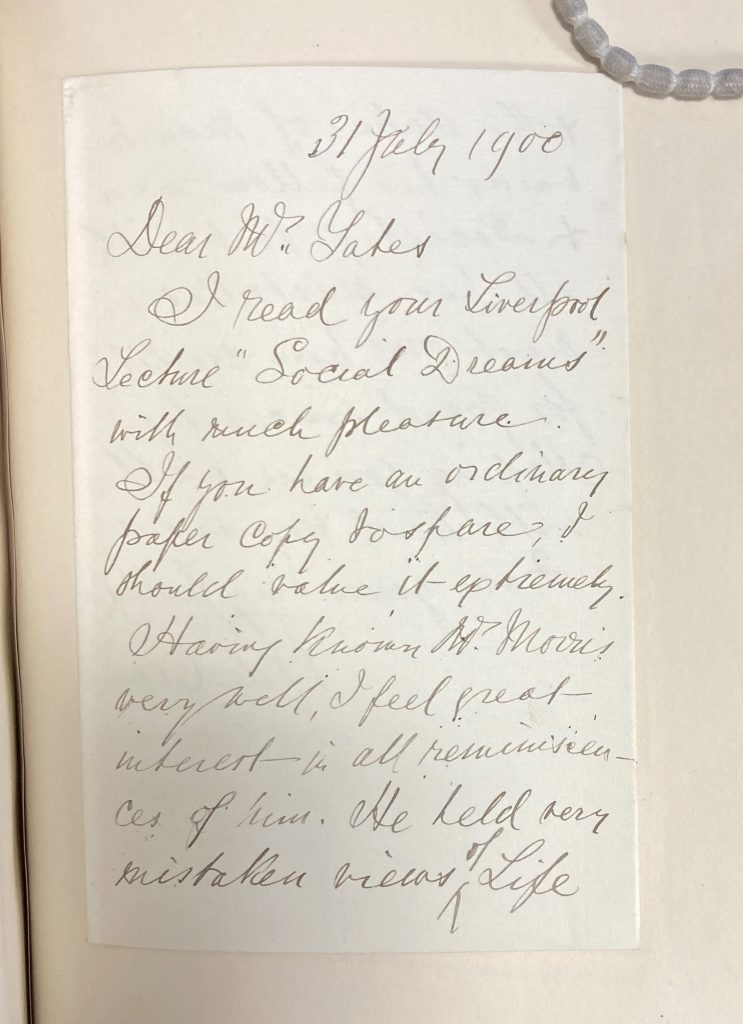

The correspondence pasted-in on the ample blank endleaves includes letters from University of Liverpool professors Andrew Melville Paterson (Professor of Anatomy), Rubert William Boyce (Chair of Pathology), Robert Priebsch (Professor of German) and Jesse Alfred Twemlow (Lecturer in Palaeography and Diplomatic), as well as from Thompson Yates’s friends and family. There is also a letter from the binder himself. Many of Thompson Yates’s books are bound by Roger de Coverly, who also undertook binding work for the subject of Thompson Yates’s speech, William Morris, and so knew him personally. De Coverly expresses agreement that Morris’s views on “life and the duties of man towards his fellow men and society” are mistaken, but writes that “with all his mistakes, we must give him credit for grand sincerity” (Morris too, it seems, had mixed feelings about De Coverly).

The most valuable portion of Thompson Yates’s library was catalogued in 1896 by University College Liverpool librarian, John Sampson. As well as one item listed in Sampson’s catalogue, Special Collections and Archives now holds 17 fascinating – if somewhat more everyday – items from his library, including books by Thompson Yates himself, as well as works by his friends and family members. As with Social Dreams, many of these books were published in Liverpool, and many of them have been added to in the form of pasted in correspondence and images. Indeed, as I hope the above begins to suggest, this relatively small acquisition opens a number of doors of enquiry and reflection. If anyone reading this has any interest in exploring behind any of these doors further we would of course welcome enquiries.