In the spring of 1936 Philosopher, Science Fiction author and University of Liverpool alumnus Olaf Stapledon wrote a letter that he hoped would change the world. On the International Day of Peace 2024, we reflect on this fascinating piece of history: what it said, who it was sent to, and what we can learn from it.

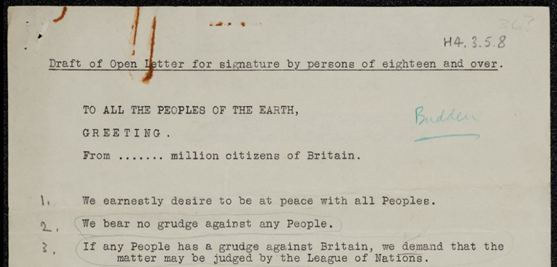

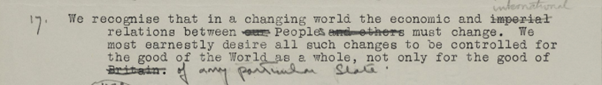

Olaf Stapledon’s ‘Open Letter to All the Peoples of the Earth’ is an incredible document: capturing a moment in time that feels at once antiquated and surprisingly prescient. Written in the shadow of the First World War, and just three years before the dawn of the Second, Stapledon proposes a series of points for peace. Addressed ‘TO ALL THE PEOPLES OF THE EARTH’ on behalf of the people of Britain, international cooperation, and specifically Britain’s role in that cooperation is a major theme of the piece. Some of Stapledon’s points are simple truisms: ‘We earnestly desire to be at peace with all people’, but others are more complex and progressive. There is an anti-colonial aspect to the letter, most clearly expressed by the point: ‘We do not wish our State to control any other People against that People’s will, whether by military or financial power’. Stapledon also makes the case for having national pride and unity, but that our ‘supreme loyalty’ should lie with our shared humanity.

The purpose of the letter may seem ambitious and a little naïve, but there was contemporary precedent for this type of letter. In correspondence related to the circular letter Stapledon cites Britian’s recent ‘Peace Ballot’ as a source of inspiration. Circulated between 1934 to 1935 the Peace Ballot, known officially as ‘The National Declaration on the League of Nations and Armaments’, was a questionnaire issued to British adults to gauge national opinion on Britian’s defence policies (McCarthy, p. 358). The ballot was answered by over 11 million Britons, approximately 38% of the adult population at the time (Ceadel, p. 810). The Britons surveyed in the Peace Ballot voted overwhelmingly in favour of peace keeping measures, including:

- Continued membership in the League of Nations;

- Reduction of armaments (if willed by international agreement);

- Abolition of military and naval aircraft (if willed by international agreement);

- Prohibition of the sale of armaments for private profit (if willed by international agreement).

While not explicitly referenced in the circular letter, Stapledon does appear to be drawing on the broadly pacifistic and peace promoting sentiment expressed by the British public in the results of the Peace Ballot. Some of the results of the Peace Ballot are reflected more specifically in Stapledon’s points for peace, particularly his emphasis on the League of Nations as a peace-keeping body. So, while Stapledon’s ambitions and sentiments appear optimistic, they are also grounded in both form and concept in the political reality of his time.

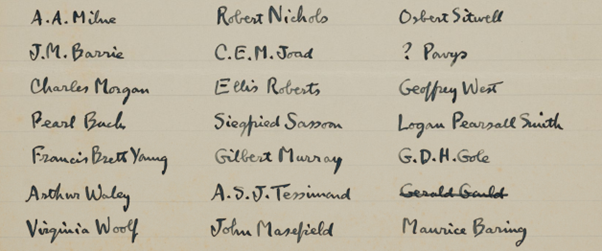

The copy of the letter that we have in Stapledon’s archive held at the University of Liverpool’s Special Collections and Archives comes complete with a list of recipients Stapledon intended to send the letter to so they could provide feedback on the piece before it was widely distributed. This list features many well-renowned public figures, from curator and scholar J. Rendel Harris to social campaigner Doreen Wallace, to authors W.H. Auden, T.S. Elliot, and Aldous Huxley. In researching the letter we were compelled to uncover if these letters had been sent out, and if so, if any copies survived in the archives of the recipients. We were able to find responses for two of the biggest literary giants on Stapledon’s list: H.G. Wells and Virginia Woolf.

These responses add an extra dimension to Stapledon’s letter in giving us the opportunity to see how his ideas were perceived by his peers. The Woolf response, which we are happy to say is published today on the University of Liverpool’s Digital Heritage Lab to mark the U.N.’s International Day of Peace, is polite but with a healthy dash of scepticism. She notes:

‘I was very glad to sign it [the letter], & hope it will have more affect than such letters generally have.’ (University of Liverpool, Special Collections and Archives, OS/H2/A32/1)

Woolf appears to approve of the political sentiments of the circular letter but has misgivings about the impact that it will have. In reflection of this, Stapledon’s optimism seems somewhat out of step with contemporary feeling, or at least the contemporary feelings of Virginia Woolf.

The cynicism of Woolf’s response is shared by Wells’, which is similarly cordial but considerably more critical. Provided by Wells’ archive at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, Wells makes comment on Stapledon’s repeated references to the League of Nations, writing:

‘Do for God’s sake forget about the League of Nations – […] escape from the nationalist and diplomatic conventions that fester in Geneva.’ (Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, MSS00071 H.G. Wells Papers, 1845-1946, Box 46, Folder WS57)

While otherwise supportive of Stapledon’s ideals, Wells’ objection to the League comes across all the more strongly. This scepticism would, of course, prove to be warranted by the League’s ineffectuality and eventual dissolution. Wells seems to be steering Stapledon away from reliance on bureaucratic institutions in his points for peace, a viewpoint Stapledon himself seemed to share. The University of Illinois archive provided not just Wells’ reply but also the copy of the letter that Stapledon sent to him. In addition to the circular letter which matches the University of Liverpool Special Collection and Archive’s copy in its typed content, Stapledon also wrote a brief letter to Wells directly indicating some of his own doubts on the project. In this letter he questions this emphasis on the League, stating: ‘Maybe the League of Nations Union approach is the wrong one’ (MSS00071 H.G. Wells Papers, 1845-1946, Box 34, Folder S-450).

So, while Stapledon does appear to have been influenced by the results of the Peace Ballot, he was seemingly concerned about invoking the League of Nations in the same way that that referendum did. Additionally in this letter to Wells, Stapledon describes the circular as a ‘very rough draft’, and the copy we have in the archive is testament to this. Although the typed content of the two copies of the circular letter are identical, the archive’s copy is replete with Stapledon’s handwritten notes and editing. Interestingly, the emphasis on the League of Nations remains, but it is difficult to say whether these handwritten annotations were made before or after Wells sent his reply.

Sadly, we have not been able to find any evidence that Olaf Stapledon’s circular letter was published anywhere after this initial feedback from his peers. Perhaps Stapledon lost faith in the idea, perhaps the expense of the project proved too much, perhaps he was diverted by other commitments. Despite the many questions that remain about the letter, it is a wonderfully hopeful document: a testament to the enduring desire to see peace realised. In the late 1930s, in the face of rising fascism in Europe, Olaf Stapledon wrote a letter to all the peoples of the Earth to show that the people of Britian wanted to live in harmony with them. Almost ninety years later, this sentiment is still a powerful one. As we celebrate the International Day of Peace, it is worth reflecting on Olaf Stapledon’s letter to think about how we can continue to build a more peaceful world for ourselves in 2024.

References:

Martin Ceadel, “The First British Referendum: The Peace Ballot, 1934-5”, The English Historical Review, 95: 377, 1980, pp. 810–39.

Helen McCarthy, “Democratizing British Foreign Policy: Rethinking the Peace Ballot, 1934–1935”, The Journal of British Studies, 49: 2, 2010, pp. 358–87.

If you would like to view Stapledon’s draft letter and Woolf’s response, click on the following link which will take you through to the Stapledon archive on the University of Liverpool’s Digital Hertiage Lab: Olaf Stapledon Archive – University of Liverpool Digital Heritage Lab

Blogpost written by Faye Lynch