The Rathbones of Liverpool were a family of non-conformist merchants and ship owners, whose sense of high social consciousness led to a fine tradition of philanthropy and public service. Their family home was Greenbank House, on the Toxteth Park estate, from the late 18th century until 1944, when it was donated to the University for student accommodation. The Rathbone Papers in the University of Liverpool’s Special Collections and Archives are the records of several generations of the Rathbone family, incorporating papers relating to their works of social and political reform, their business ventures, and their family life, dating from the late 18th to the late 20th centuries. For a family with such wide reaching concerns and interests it is not surprising their archive provides a fascinating insight into the impact of the First World War, on both those who fought and those who remained on the home front.

Hugh Reynolds Rathbone (1862-1940) – a grain merchant who served as a member of the Royal Commission on Wheat Supplies during the First World War – collected notes and correspondence relating to Rathbones serving in the military, which are now held in the archive (RPXIX1.51-60). His son, Richard Reynolds Rathbone, served in the 6th King’s Liverpool Rifles, and was considered lucky by his family to have been wounded in action and brought to a London hospital. He later received the Military Cross for bravery. Another, more famous, familial recipient of this prestigious award was the actor, Basil Rathbone, who was commended for “conspicuous daring and resource on patrol” after conducting daylight raids in 1918. Basil’s younger brother, John, was killed in action in the same year. Their cousin Gilbert Benson Bolton was similarly unfortunate. A Lieutenant in the 8th North Staffordshire regiment, he was reported missing in November 1916 after the battle of Grandcourt. Gilbert’s servant wrote to his mother Nina Rathbone Bolton describing how he became a “most popular officer & presented all the qualities of a true British soldier…I still hope that he may be alive & that the family may hear news of his safety”. Nina herself was more realistic about the chances of a happy ending in her letter to Hugh of 9 February 1917, writing movingly that,

to me he was a kind of second daughter…one of his great qualities was cheerfulness & that is how I always saw him even during the last leave at home and going back… I have recently found a Louis Stevenson sentence which entirely applies “a good influence in life while he was still among us; he had a fresh laugh; it did you good to see him; & however sad he may have been at heart, he always bore a bold and cheerful countenance & took fortune’s worst as it were the showers of Spring.

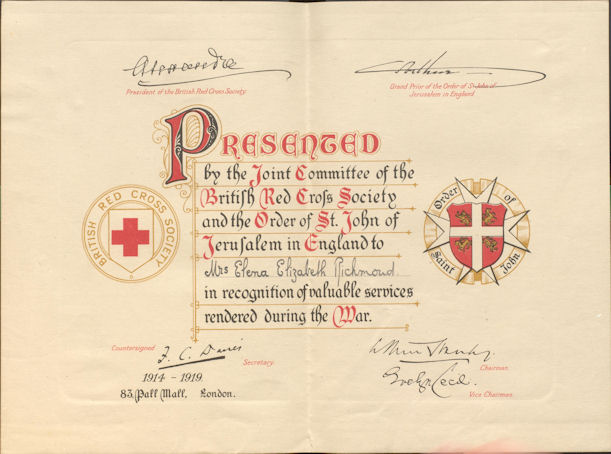

Other female members of the Rathbone clan took a more active role in the war. Lady Elena Richmond (née Rathbone, 1878-1964) exemplified the family’s tradition of social service, and was a supporter of District Nursing, as her father William VII and grandfather William VI had been. The Rathbone archive contains correspondence relating to Elena’s war service with the Red Cross Society (RP XXV.5.17.1-33), as well as a service medal and certificates she received in recognition of the ‘valuable service rendered’ and in commemoration of her being inscribed upon the Red Cross Roll of Honourable Service. Elena worked as part of the Enquiry Department for the Wounded and Missing, and after the war received a letter from the Red Cross outlining the scale of the work she had helped to accomplish. From April 1915 until March 1919, the department had received 342,248 enquiries from relatives and friends, and produced 384,759 reports, a process which had entailed the interviewing of between four and five million soldiers. As the case of Gilbert Benson Bolton illustrates, these reports did not often bring the recipient the news they were hoping for, but the Director of the Red Cross wrote,

It is abundantly evident from thousands of grateful letters…that our work has been thoroughly appreciated. If you could see these letters, I’m sure you would realize that the work you have carried out…dull and wearisome as it must often have seemed, has not been in vain, for it enabled us in very many cases to alleviate terrible anxiety and substitute certainty for suspense.

Elena’s aunt Eleanor Florence Rathbone (1872-1946) is often considered to be the true heir of her father, the social reformer and Liberal MP William Rathbone VI (1868-95). As the secretary of the Women’s Industrial Council in Liverpool before the war, she campaigned against low pay and poor conditions, and in 1909 she became the first women to be elected to the City Council.

Once war broke out, the social dislocation which resulted brought into focus the inadequacy of provisions for the dependents of soldiers and sailors, a situation Eleanor was already aware of through her social work as a home visitor for the Liverpool Central Relief Society, which often entailed working with the wives of dockers. Eleanor’s cousin, Herbert Rathbone, was the Lord Mayor during this time, and turned to Eleanor to expand the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association; the Liberal government had approved ‘separation allowances’ for the families of volunteers but had organised no machinery with which to administer them. Eleanor used her contacts to ensure advance payments in the hope that the War Office would honour them. That not only did they do so, but in time formalised and centralised payments through the new Ministry of Pensions, was testament in large part to Eleanor’s organisation in Liverpool.

Even after central government had stepped in, the organisation carried on, and at the end of the war Eleanor helped create the Liverpool Personal Service Society to act as a model for this type of family-based social work. Eleanor herself met a huge number of people through these channels, as she conducted a good deal of the practical work herself and often heard problem cases.

Throughout the war I had to investigate and report to the War Office…on practically every case in which a Liverpool soldier deserted his wife.

In 1917 Eleanor Rathbone established the Family Endowment Committee to look into the nature of this type of poverty. Its report Equal Pay and the Family: a proposal for the National Endowment of Motherhood (1918) launched the campaign for family allowances. Eleanor’s experiences in Liverpool in the First World War led directly to the introduction of these payments in the aftermath of the Second World War. What we today know as Child Benefit sprang from Eleanor’s desire to help those women who had endured the hardships of managing households on the irregular wages of the casual worker, only to be left vulnerable to widowhood or desertion in wartime.