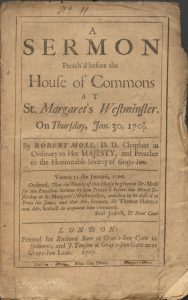

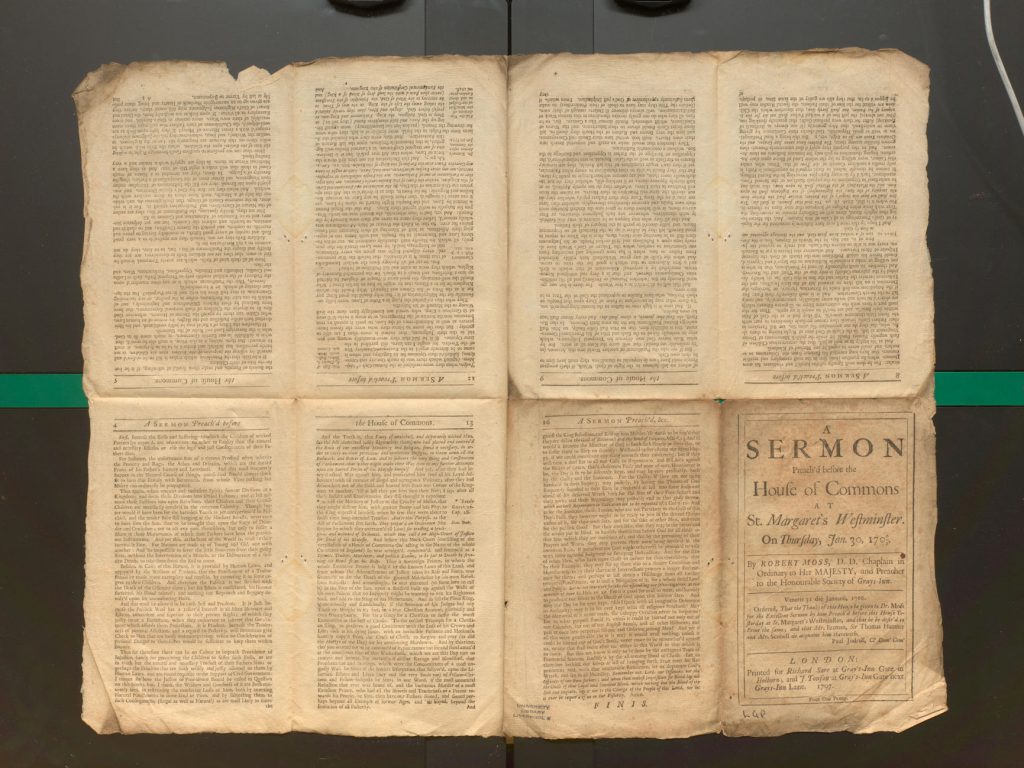

Early printed books – from the start of printing in the fifteenth century up to the early nineteenth century – were produced very differently from modern, machine-printed books. They were printed by hand on large sheets of paper, with several pages on each side, as shown by this sermon preached to the House of Commons in 1707.

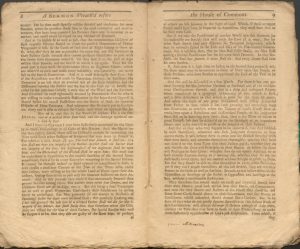

The sheets were folded into gatherings – quires – and sewn together by the binder to make the book ready for binding, as in our second copy of the same sermon in the form of a stitched pamphlet.

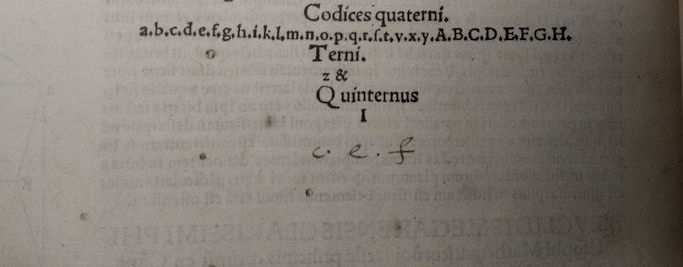

Before being folded into quires, as the individual sheets were being printed, the first page on each sheet was marked (‘signed’) with a letter of the alphabet. That way, when the quires came to be sewn together to make up the full book, the binder had a guide to help him retain the correct order – putting quire A, before B and so on.

A register of all the letters used by the printers was often included, as shown in an edition of Euclid printed in Paris in 1516. Only 23 letters were used – leaving out I or J, U or V, and W. This printer’s alphabet – like many aspects of the earliest printed books – used the system developed by manuscript scribes, in this case to avoid confusion between similar looking letterforms in the Latin alphabet.