Anyone who has carefully studied one of our catalogue records may have spotted that the “Description” field contains a symbol that looks something like this – 2°, 4°, 8°, 12°. This number indicates what is called the “format” of the book – a term which refers to the manner in which the sheets of paper (or vellum) of which the book is comprised have been printed and folded.

As indicated in the first post in this series, books produced during the hand-press era (roughly up until early in the ninteenth century) were formed from large sheets of paper, on which several pages were printed in one go. The page would then be turned, and the corresponding pages printed on the other side of the sheet.

Books produced of sheets printed as in the example above, and folded and cut so as to give gatherings of eight leaves, sixteen pages which are then sewn together to create the full text, are called “octavo”, which is represented in the catalogue as 8° (or sometimes 8vo).

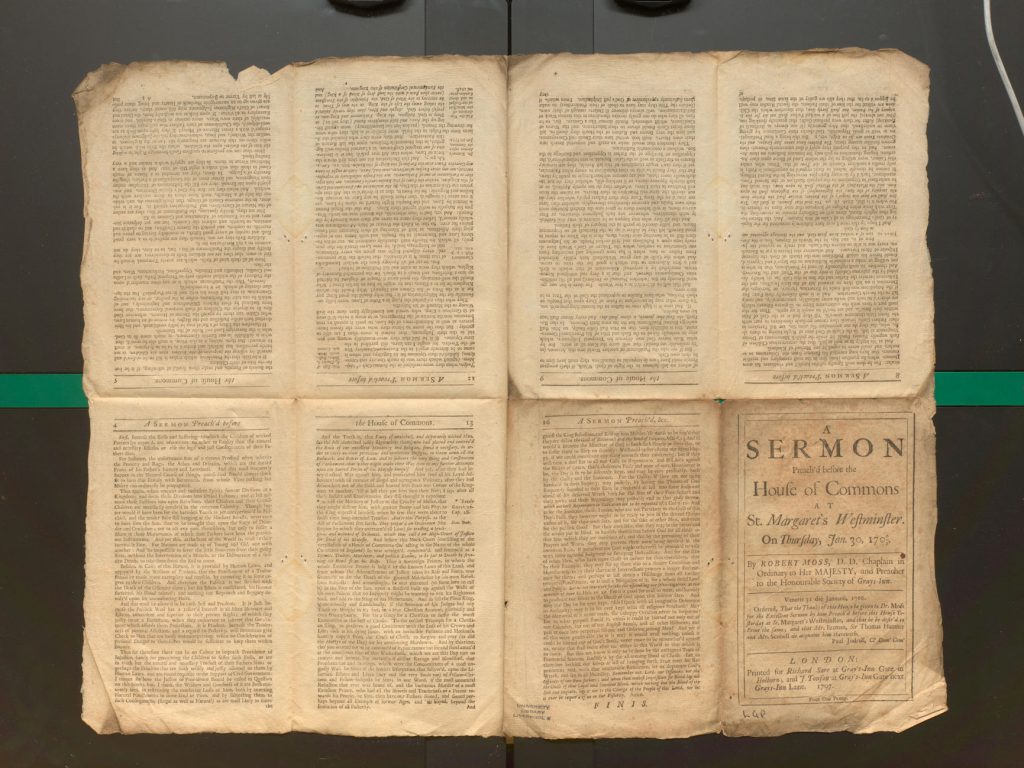

When just two pages are printed side-by-side on both sides of a sheet which is later folded once, and then cut, resulting is two leaves, four pages, the book comprised of gatherings of these leaves is called a “folio” (which is written as 2° for short, or sometimes as “fo”). In this instance, each page of the book will be half the size of the sheets used in printing. And where sheets have been printed with the text of four pages per side, and then folded twice, a book has the format “quarto”, 4to or 4°. This sheet, folded one extra time, results in four leaves a quarter of the size of the original sheet.

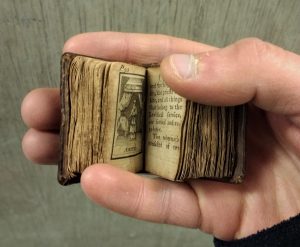

These are the most common book formats you are likely to encounter; but occasionally you might come across a book composed of leaves made from sheets that have been folded four or more times (duodecimo, 12°, 12mo,16°, 24°, 32°, up to 128°!).

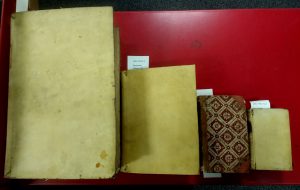

Evidently a folio book is likely to be larger than a quarto, which is likely to be bigger than an octavo, and so on – but beware, the size of the finished product will depend upon the size of the original sheet. During the hand-press period this varied, and there can be quite a bit of variation in size within any single format as a result (we normally say folio books range between about 30.5 cm and 48 cm, for example).

The format – and therefore size – of a book can provide a clue as to whether the printer was treating the book as a luxury good, or a commercial venture for less-wealthy readers. Smaller format books can be printed more quickly and use less paper and less binding material, so they can be sold more cheaply.

Similarly, the format of a book can provide an indication of its use – a book intended to be shown-off, or read by many people at once, is more likely to be produced in a large format; whereas a book intended to be carried on one’s person would need to be small and portable. To take two examples from SC&A: Inc.CSJ.D13/OS is a two-volume Bible printed in Nuremberg in 1475, which stands nearly half a metre tall, whereas 2017.a.028 is a copy of John Barnes’ The new London chemical pocket-book (1844) “adapted to the daily use of the student” is 17 cm.

Cataloguers use marks within the paper to help determine how many times a single sheet has been folded, a process we’ll cover in greater detail in later posts – so watch this space!