This post was written by second-year history student Charlotte Stephenson.

As part of my studies I have been completing a placement at Special Collections and Archives. During this time, I have been learning about the cataloguing process through box-listing and scanning a variety of material relating to the university’s halls of residence and societies, and in this blog post I wanted to share the items that I found particularly interesting.

Salisbury Hall information booklet

Once part of the Carnatic Halls of Residence, situated close to Sefton Park, Salisbury Hall was built on the site of the 18th century residence of slave-trader Peter Baker. The first page of the information booklet outlines Baker’s capture of the Carnatic ship, motivated by the need to pay off his debts that he had amassed while building a poorly constructed boat. The profits that Baker gained from the Carnatic’s booty allowed him to build the original Carnatic Hall, which burned down in 1889. A second Carnatic Hall was built by Walter Holland following the fire, though this was demolished in 1964 by the university in order to use the site for student accommodation. Salisbury Hall was demolished in 2019 along with the other residences that comprised the Carnatic Halls, though sources such as this information booklet and yearly student photographs can give us an impression of student life in these halls.

This information booklet appears to date from the mid-1960s, shortly after Salisbury Hall opened its doors to students. The strict procedures and guidelines paint a very different picture to our current perception of student life with no late-morning lie-ins or excessive noise at night-time, though one can imagine that these rules may not always have been followed by students. The advice appears to have been written for the women students who inhabited Salisbury Hall, with “gentlemen visitors” banned from the students’ bedrooms from 10:30pm onwards. Not only was contact with male students and visitors limited, Salisbury Hall residents were also forbidden to eat meals in their bedrooms, they required the warden’s permission to throw parties and the students were asked to vacate their bedrooms by 10am on weekdays to allow for cleaning. Despite the stringent regulations in place, the information booklet goes on to describe a vibrant social scene in the halls with dances, socials events and meals organised for the students to enjoy, and a variety of opportunities to get involved with representing the hall.

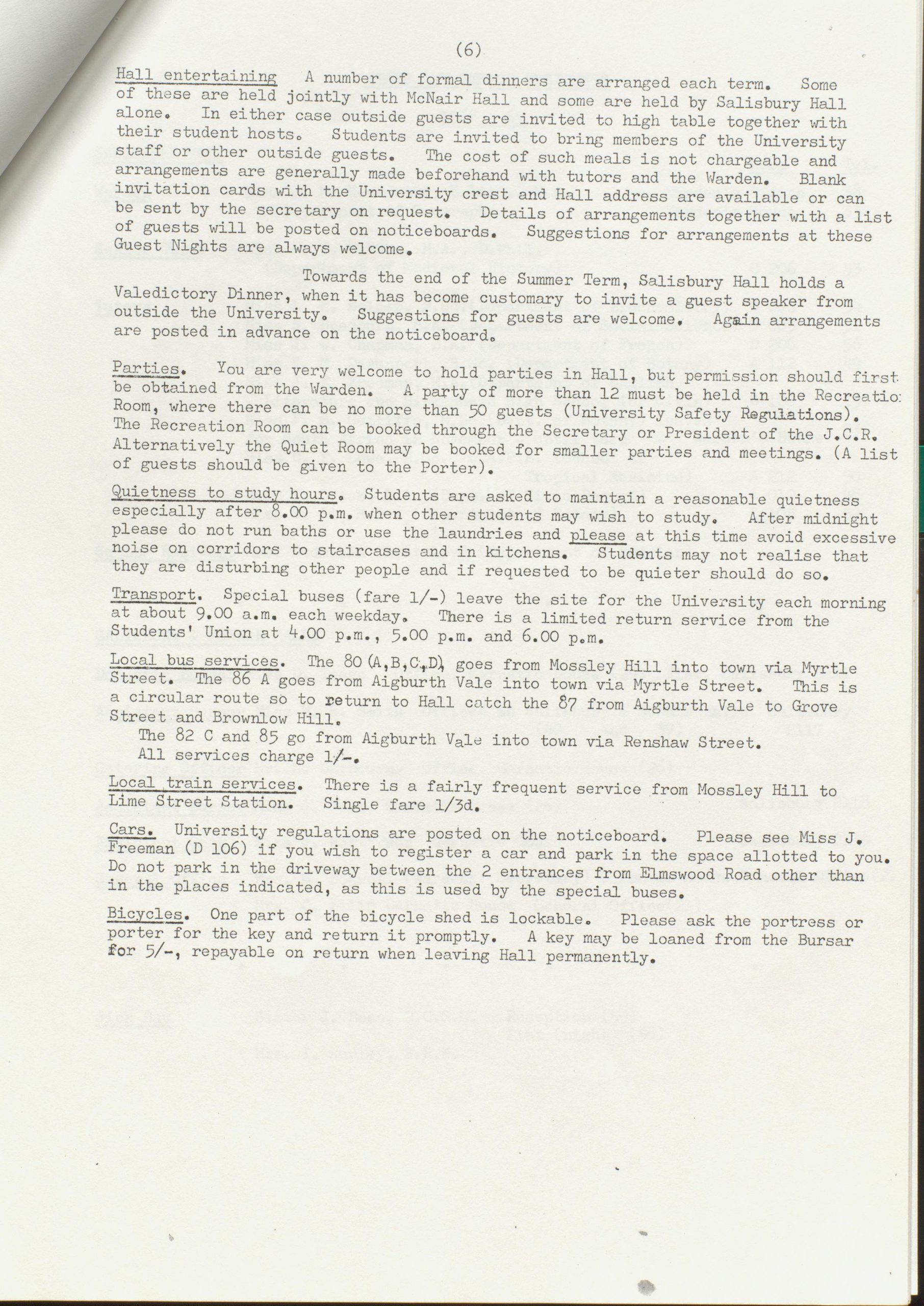

Rathbone Hall photograph (1981-1982)

Perhaps the most humorous image I was able to catalogue during my placement was the 1981-1982 photograph of the residents of Rathbone Hall (now the site of Greenbank Student Village). On the surface, it appears much the same as the numerous other yearly student photographs, though if you look closely, one opportunistic student can be seen through a window, posing with a lampshade on their head. Their prank will now be forever immortalised in the university’s archives for future visitors to enjoy.

Chemical Society photograph (1919-1920)

During my placement, I have been able to work with photographs of students taken over a century ago. A particularly interesting example is the photograph of the Chemical Society, taken between 1919 and 1920, just a year after the conclusion of the First World War. The photograph depicts only two women students, at a time when interwar advancements to the opportunities of women were balanced against a backlash of oppression and concerns over their involvement in public life. Looking through the yearly photographs of the university’s societies and halls of residence, we are able to see the gradual increase in women’s admittance into higher education, and a greater diversity of ethnicities, nationalities, gender, and class in the student body.