This post was written by second-year history student Charlotte Malloy.

Over the last few weeks, I have been completing my HIST200 placement at the University’s Special Collections and Archives. I have been working on a project which has included recording details of letters found in the printed book collection. I have looked at letters from books in multiple collections within the Special Collections.

The letters found inside books can be really useful in understanding the relationships between authors, publishers, collectors and friends. They can help us to understand why a book had ended up in an individual’s collection whether that be because they bought it for collecting purposes, they were a member of a society, they were offering advice to another scholar of what to include in their work and received the final publication or simply that they received it as a gift.

The majority of the letters I have looked at only show half a conversation as letters are rarely given back to the sender, so it has not always been easy to fully understand the context of the correspondence simply by reading the letter. Further research about individuals and organisations has helped to make this clearer.

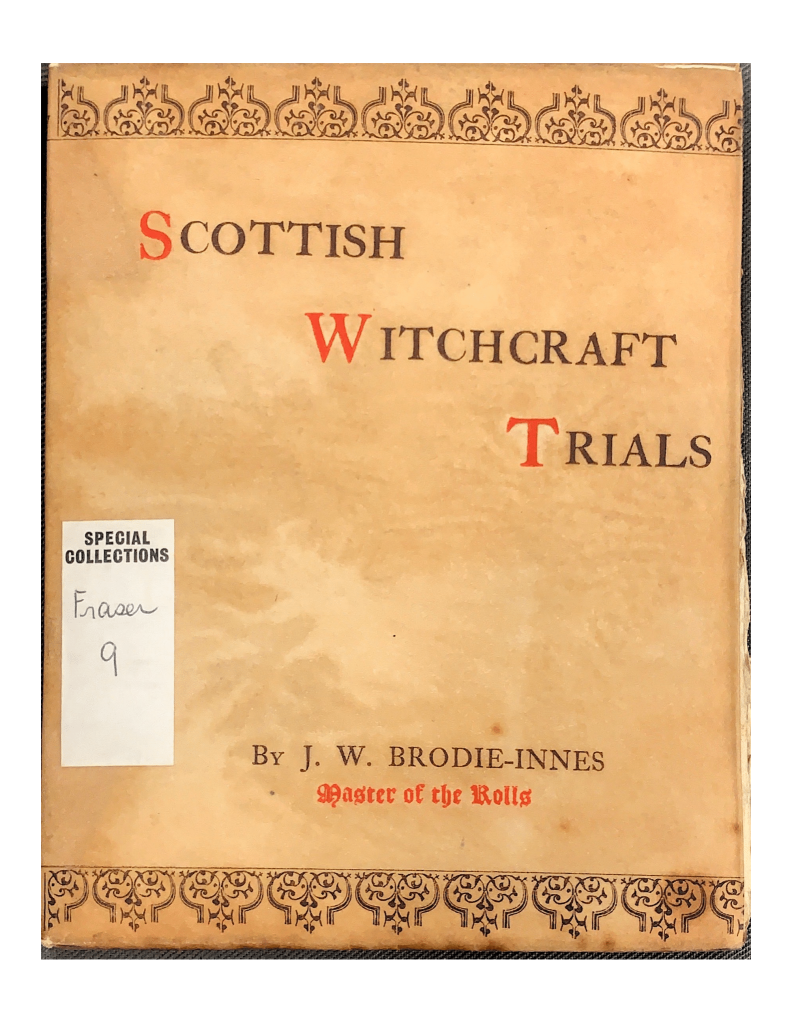

One of the collections I have looked at belonged to John Fraser (1836- 1902), Secretary of the printing and publishing department of Cope’s Tobacco Company in Liverpool. The letters in Fraser’s collection tend to be more personal as rather than in relation to business. It is clear from the letters that Fraser was known for collecting books, and people gifted him them for this reason. One example being John Lane sending a copy of ‘Scottish witchcraft trials. Read before the Sette at a meeting held at Limmer’s Hotel, on Friday 7th November 1890’ by J.W. Brodie (SPEC Fraser 9). In his letter Lane says he has sent Fraser the book in reward for helping him and gifts him the book as he knows he has a love of books. Fraser also tended to be sent books that related to his interests, Scottish literature was one of them. Fraser’s correspondents were often sent tobacco in return, this may have been the case with John Lane.

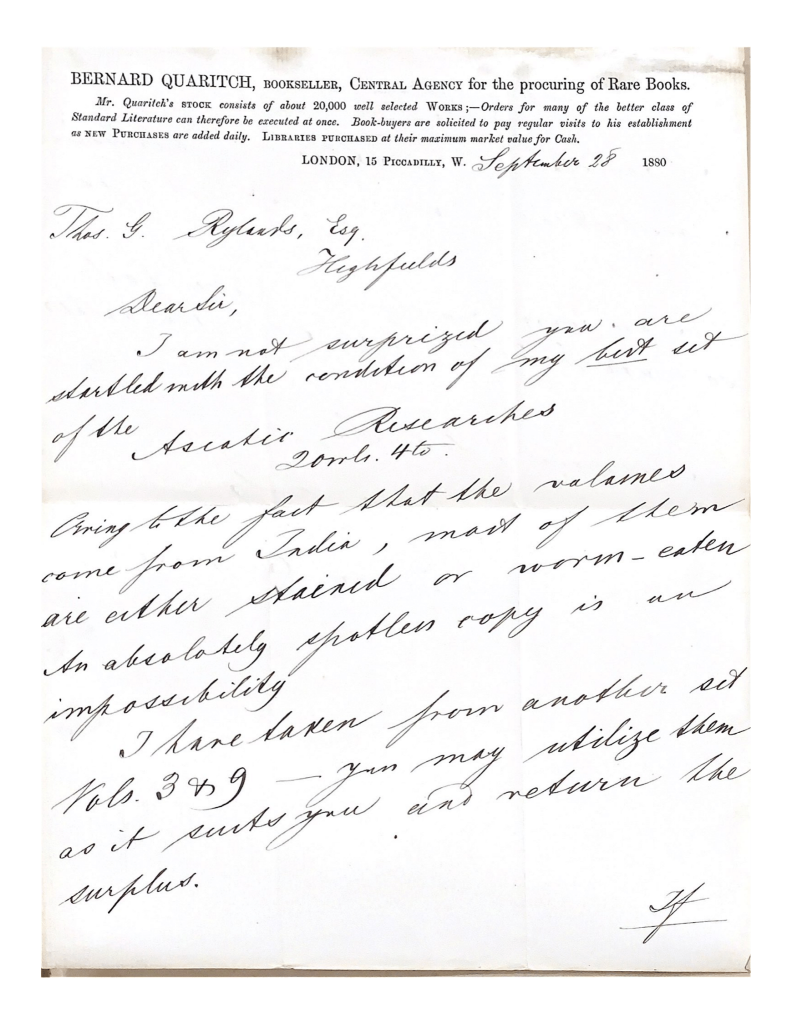

Another collection I looked at belonged to Thomas Glazebrook Rylands (1818- 1900), a wire-manufacturer in Warrington. His collection is significant to the University’s library as it was their first major bequest. The letters in Rylands’ collection are not personal like Fraser’s were but include more contact with publishers as they advertised books to him and responded to requests he had made. One interesting correspondence comes from Bernard Quaritch, a bookseller, apologising to Rylands that the books he had ordered arrived from India stained and worm eaten and said he would send different volumes instead. This letter was found in ‘Asiatic Society of Bengal’ (SPEC RYL.P.8.01), clearly showing that this promise was kept.

William Noble (1838- 1912) who was Treasurer of the Mersey Docks and Harbour Board is another individual whose collection I have looked at. The letters in Noble’s collection differ to those of Fraser and Rylands as most are now stored separately from the books they were found in, and are grouped, if possible, together with other letters from the same sender. One example of this is the letters from Henry and Emily Daniel from The Daniel Press of which there was a large amount. These letters typically include receipts for books Noble purchased and inform him of any other books the company believe he would be interested in. The number of letters received from The Daniel Press gives an idea of the size of Noble’s collection as he had purchased so many books from one company, which would be replicated with others.

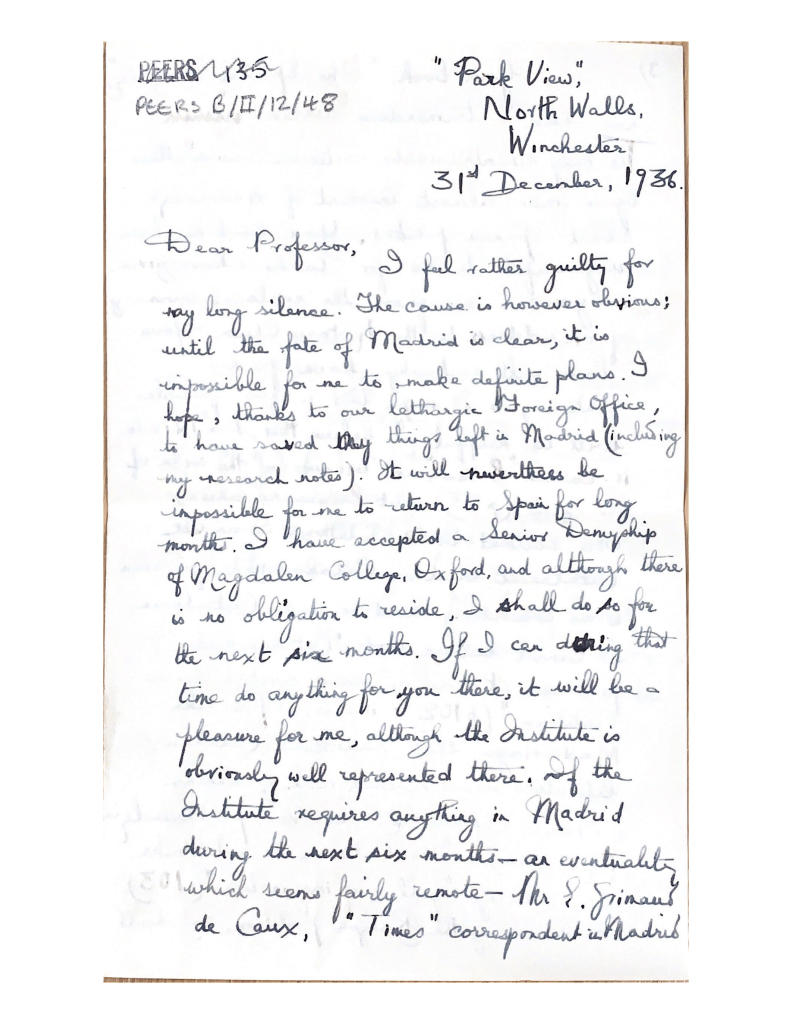

Another collection I looked at belonged to Edgar Allison Peers (1891- 1952). Peers’ work and therefore his collection focused on the Spanish Civil War, as he wrote about the subject in books and newspapers, he was also a Lecturer in Spanish at the University of Liverpool from 1920. The letters from Peers’ collection are stored separately from the books they were found in to be kept with other relevant material such as newspaper clippings. A notable letter in this collection comes from an unknown sender and was found in Peers’ book ‘The Spanish tragedy 1930-1936: dictatorship, republic, chaos’ (SPEC Peers 135). In the letter the writer spoke of his current situation having left Spain and was sure he wouldn’t be able to return for many months. This letter is valuable as it came from someone living during the civil war, talking first-hand about their experiences. This would have helped Peers in his own work.

Reading the letters found in books from the printed book collection has given me an insight into the lives of the individuals who collected them. The letters highlight the dedication they had to growing their collections, which are now such a valuable resource for researchers.