In the wake of this month’s celebrations marking the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, we pay homage to the Bard with a look at some editions of his works held here in Special Collections and Archives.

This post indulges our library assistant’s own particular predilection for one of the last plays to be penned, The Tempest. Believed to have been written between 1610 and 1611 – and first performed in 1611 at the Royal Court – The Tempest is often cited as the last play believed to have been written solely by Shakespeare. The two plays from 1613, The Two Noble Kinsmen and Henry VIII are often reputed to have been written in collaboration with John Fletcher. Somewhat tricky to categorise due to its complex blend of poignancy, comic farce, violence and fantasy, The Tempest is often discussed in terms of its motifs, as well as the contextual significance these are accorded by commentators, rather than in terms of its dramatic structure.

The epigraph of our title, which is arguably one of the most famous in both this play and the whole Shakespeare canon, comes from Act IV, scene i. Here Prospero cuts short the play-within-the-play, or ‘revels’, he has orchestrated and instead looks to certain pressing formalities to be dealt with before the play’s conclusion. These include the impending nuptials of his daughter and her suitor Ferdinand, an ostensibly joyous occasion which nevertheless signifies a loss to Prospero as a father, and the treachery of Caliban, a creature of uncertain nature and Prospero’s erstwhile serf.

Prospero’s words could be read as a metaphor for both the impending conclusion of the performance and, more broadly, the ‘conclusion’ of all things, animate or not, in death, decay or the steady attrition of time. The Tempest, in blending the fantastical with the profundity of socio-political commentary, has retained its appeal throughout history just as has its author.

Prospero:

[…] Our revels now are ended. These our actors, As I foretold you, were all spirits and Are melted into air, into thin air: And, like the baseless fabric of this vision, The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces, The solemn temples, the great globe itself, Ye all which it inherit, shall dissolve And, like this insubstantial pageant faded, Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff As dreams are made on, and our little lifeIs rounded with a sleep.

[IV:i]

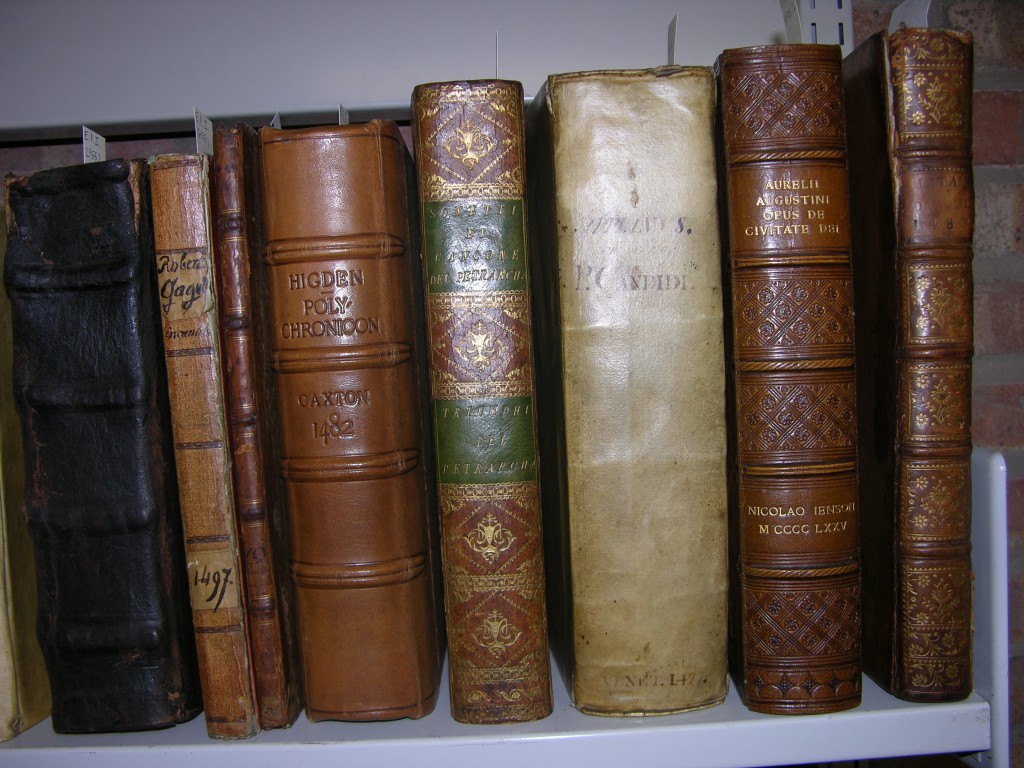

Our collection of early printed books contains editions of Shakespeare’s works from as early as 1623. SPEC Y62.5.14 comprises two plays reproduced from the First Folio, The Taming of the Shrew and All’s Well, That Ends Well, and declares on its title page, “Mr. William Shakespeares comedies, histories, & tragedies; published according to the true originall copies”.

Our earliest full collection of Shakespeare’s works dates from the following decade. Printed in London in 1632, the Second Folio SPEC Morton 334 is of especial value to those with an aesthetic sensibility, with its gilded edges and marbled front- and end-pages. It was gifted to the University Library in 1969 by Robert George Morton, founder of the Argosy and Sundial Circulating Libraries and benefactor of our Morton collection.

Full details of incunabula and early printed books held in SC&A are available on the dedicated webpage, which can be accessed via our homepage.

For a further exploration of Shakespeare’s 400-year legacy, see Catherine Tully’s post on the University’s Student News webpages.