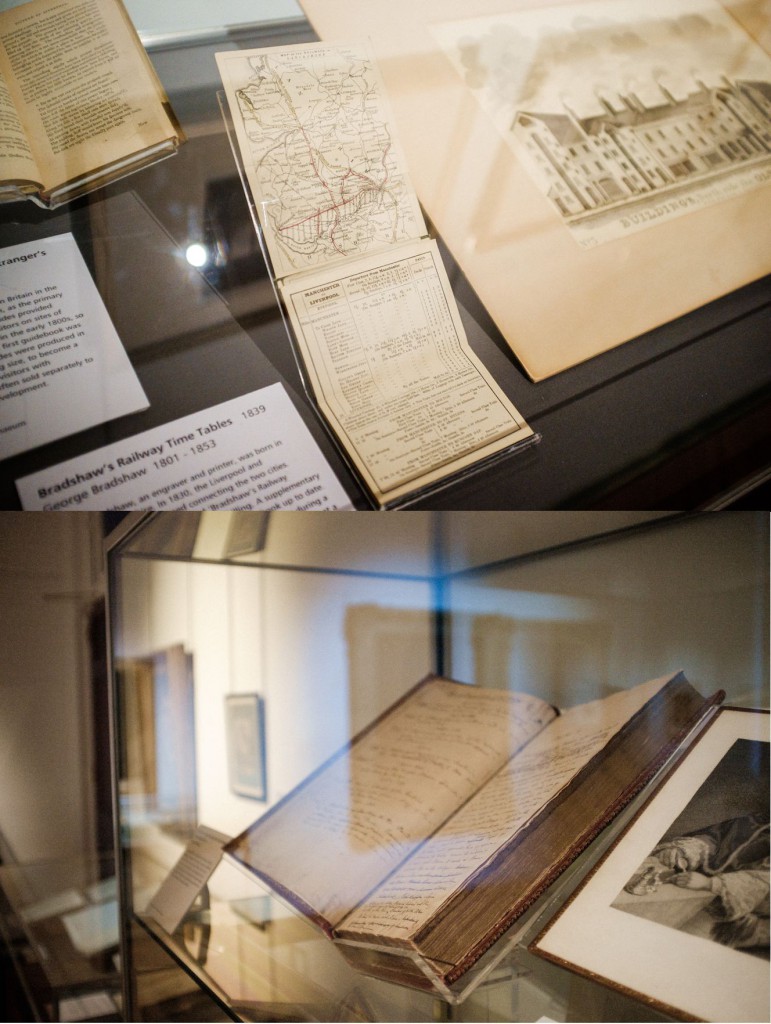

Special Collections & Archives was a contributor to the recent Knowledge is Power exhibition at the Victoria Gallery & Museum, lending several items from its collections. Focusing on the development of two of Liverpool’s oldest surviving cultural institutions, the Athenaeum Club and the Liverpool Medical Institution, the exhibition showed how libraries shaped elite culture in the Liverpool, but also how the power of books was opened up to the wider population in the reforming decades of the early Victorian era. The exhibition items loaned from Special Collections & Archives, chosen to reflect the long history of libraries in Liverpool, included a view of the Lyceum building (1 Bold St) painted onto the fore-edges of a printed catalogue.

What are the main factors which need to be considered when preparing books for display in an exhibition such as this? Before any loan is agreed, the institution making the request must be able to guarantee appropriate environmental conditions and security. The relevance of the item for the narrative context of the exhibition is also important. How will it be displayed? What is the opening required in the book? Will text, illustrations or bindings need to be shown? Special Perspex cradles are constructed for each item based on the specific opening required; large, heavy books will need a cradle with a thick lower edge to prevent the text block moving; in the example of the Lyceum catalogue mentioned above, the mount needed to display the book at such an angle and with just the correct amount of light to allow the viewer to see the fore-edge painting without exposing it to damage.

Of course, there would be no question of considering mounts and cradles if the basic condition of an item meant it was too fragile to display at all, and perhaps the major factor influencing exhibition loans is the physical condition of the item itself. At a basic level, the physical state of a document is influenced by the manner of its production and this, along with knowledge about the impact of environmental factors upon materials, informs how we look after collections and make them accessible. Special Collections & Archives contains many different types of material: medieval and modern manuscripts; early and finely printed books; modern printed collections including newspapers, posters, photographs and ephemera; audio-visual and digital media. These all present different preservation challenges.

It can be easy to assume that the older an item, the more at risk it is, but there are some important factors influencing physical condition which are not necessarily related to the age of the item. The technology of printing, binding and paper making remained more or less the same from the beginning of printing in the mid-15th century right up until the early 19th century. Letters were set by a compositor, inked and pushed against a sheet of paper by a hand press machine operated usually by two men, one to apply the ink and one to operate the levers. Paper was made of pounded linen rags, mixed with water and sieved, and then stabilised with animal gelatine. Books tended to be sold unbound, and though some remained in paper covers, if money allowed leather bindings were created and the text block was hand sewn with cords well secured to the boards. These processes, though laborious, used natural materials which stayed strong. However, in the 19th century the growth of a mass market and the concomitant increase in mechanisation meant linen rags couldn’t meet the demand. It was replaced by wood pulp (which is chemically and mechanically weaker) and binding also became cheaper and more mechanised. The effect of these changes can be easily seen when a flaky 19th century newspaper, discoloured by acidification, is compared with the thickness of laid (chain-lined) paper in a 16th century church Bible.

It stands to reason that books couldn’t be exhibited at all if they weren’t cared for properly on a day to day basis. To preserve material, we need to understand its physical composition. In Special Collections & Archives our holdings date from the 1st century BC to the present day and include papyri, parchment (prepared animal skin), vellum (specifically calf skin- from the French veau), photographs, and audio-visual material and digital files. Even in one single printed book there will be different types of paper, glue, ink and binding materials, which will decay at different rates. The chemical stability of parchment and vellum is good, but is very susceptible to the impact of moisture in the atmosphere, and as humidity fluctuates the material will crinkle (known as cockling).

Environmental guidelines are set down in Public Document 5454 – A guide for the storage and exhibition of archival materials. Light is of course the main cause of damage, explaining the low levels of light in exhibitions. Coupled with humidity and temperature, the stability and level of these environmental factors are key considerations the borrowing institution must agree to maintain. Light damage is cumulative and irreversible – cellulose weakens, paper bleaches and darkens, and ink in type and illustrations will fade. UV light is the most damaging, so it is important that no natural light enters storage areas and artificial light is only turned on when needed. Protection can also be provided via storage in archival quality boxes. Items on long term loan in exhibitions will have the pages turned regularly.

Temperature and humidity are mutually dependent – a high humidity level will hasten chemical reactions and mould growth, whereas a low level dries out paper and parchment, making it brittle. Fluctuations are the most dangerous as materials will expand and contract as they absorb and release moisture – as well as cockled paper, the finish on photographs may crack. Photographic media benefits from very cold conditions and benefits from specialist storage, such as that available in the North West Film Archive. The ideal for a mixed media store is that conditions are controlled to achieve a temperature between 13 and 16 degrees Celsius and a Relative Humidity between 45 and 60%.

All this ongoing activity must be complemented by correct handling procedures. Although white gloves often seem to function as media shorthand for precious material, their use is not general recommended by conservators, archivists and librarians. As there is a higher chance of gloves being dirtier and affording a less sensitive touch than clean, bare hands, their use is more liable to cause damage. Archival quality plastic gloves are recommended for handling photographs. Opening books without special supports strains spines, hence the use of book cushions, snakes and weights. Familiarity with handling guidelines and use of such supports are an intrinsic part of using any special collections and archives reading room. Rules forbidding use of pens and wearing of coats are not solely based around security – ink can easily be inadvertently transferred and coats bring moisture and dirt into what needs to be a controlled environment.

What is the difference between preservation and conservation? Preservation covers the type of environmental issues we’ve considered and is perhaps best seen as an ongoing management process. Conservation is generally taken to mean a specific treatment involving intervention, which may be required in order to make an item suitable for display. Modern conservation ethics mean the historical integrity of the item is respected and professional conservators will understand both the history of an item, its production, physical characteristics and the scientific qualities of the materials it is composed of. Conservation work can include surface cleaning of pages, de-acidification, removal of old repairs, sewing, mending tears using Japanese papers, re-backing, rebinding and box making. Conservation is not about trying to restore something to a perceived original state, or trying to make it look nice – it is primarily undertaken to ensure the unique history and provenance of an item is preserved for research and for posterity.

This blog post is based on a talk given by Jenny Higham, Special Collections & Archives Manager, at the Victoria Gallery & Museum in March 2016, as part of the associated programme of events accompanying the “Knowledge is Power” exhibition.