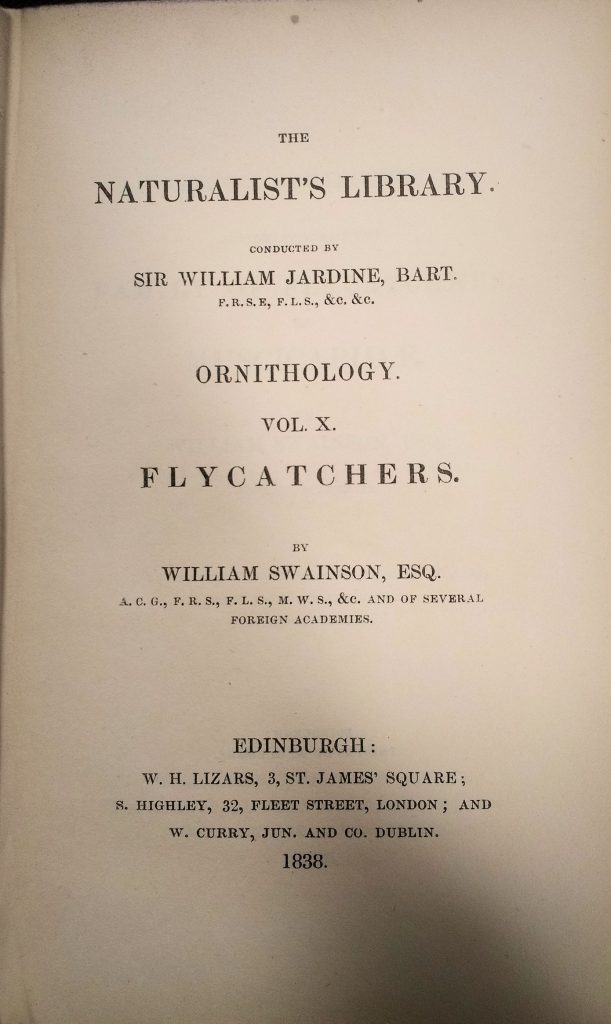

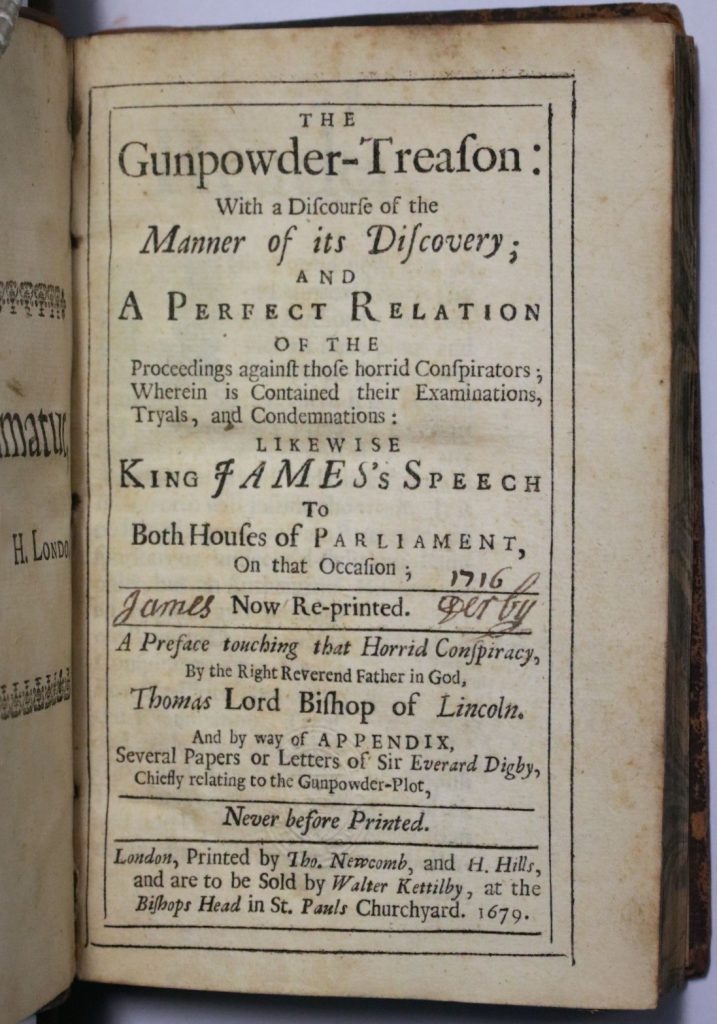

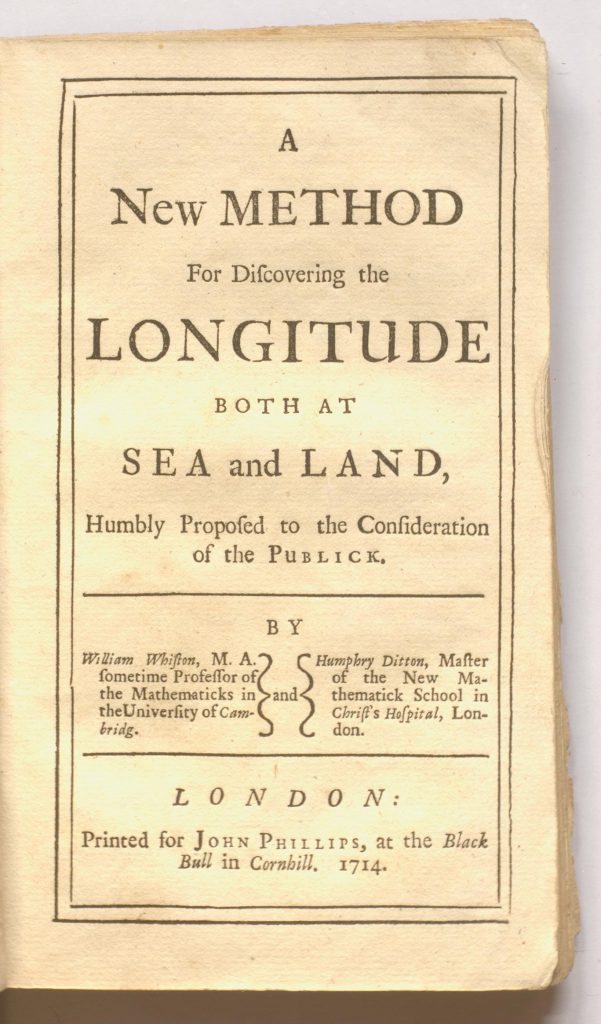

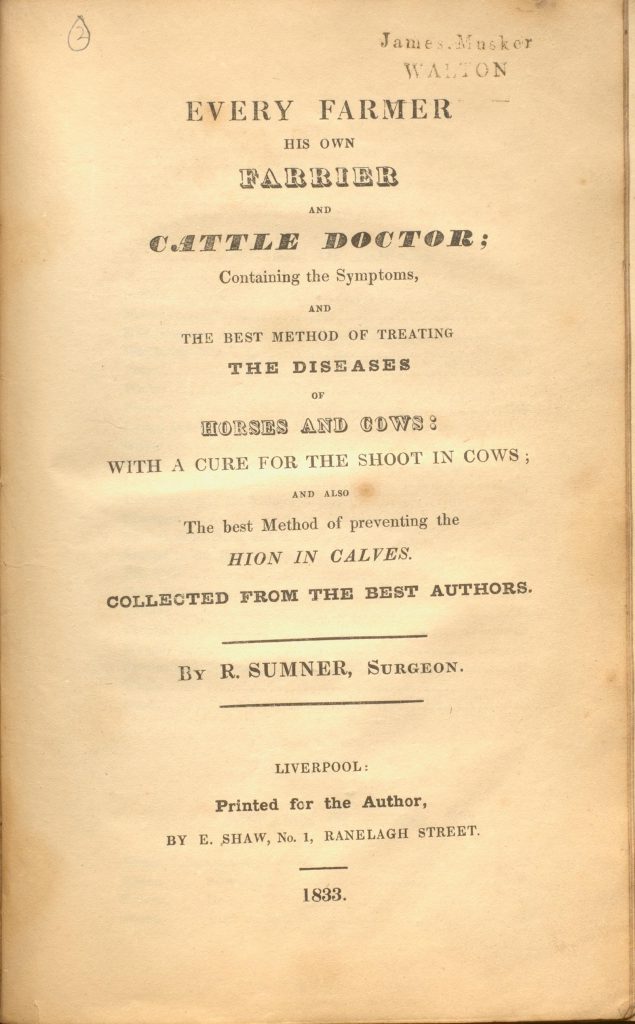

Like so many elements of book design (bindings, bookplates, typography), the appearance of the title-page has been subject to fashions, and the amount of information offered on a title-page has varied over time accordingly. For example, whilst the earliest title-pages were relatively simple, in the 17th century it became standard practice to cram as much information as possible onto the title-page – with extensive sub-titles and detailed author and publisher information, often in multiple types, and within decorative frames. This trend died off in the 18th century, as a tendency for more simply set-out title-pages (often accompanied by half titles) took its place. This pattern repeated; the 19th century saw a return to more elaborate title-pages, whereas the emergence of modernism accompanied a more stripped-back approach in the 20th century.

As engraving came to be used more widely in book illustration from the late 16th century, engraved title-pages emerged. Occasionally books contained additional engraved title-pages alongside a letterpress title-page, as in the example below.

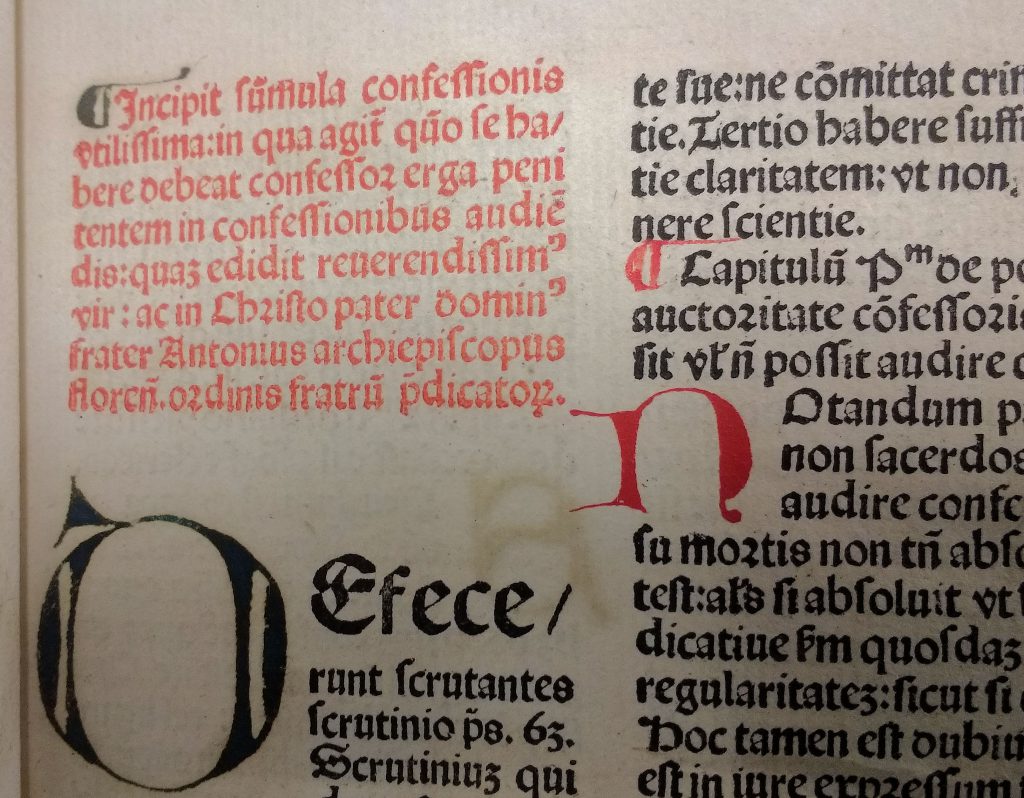

The earliest of printed books do not contain title-pages at all however; nor do most medieval manuscripts. Instead, these texts are generally identified by the “incipit” and “explicit” – the opening and closing words of the text, from the Latin verb incipere (‘to begin’) and explicitus, meaning ‘unrolled’.

Early printed books often closed with a “colophon” – a closing statement, providing, for example, the name of those involved in the book’s production (scribe, printer, publisher), and place and date of publication.

Earlier in this series we met the half-title page: here it is worth noting that the history of the half-title page, as outlined in this earlier post, also helps to reveal how it was that the title-page came to be – “printers would produce the pages of a text – the text-block – which they sold unbound”; a “blank sheet originally intended for protection came to be marked with a short-title in order to help differentiate one text-block from another, and it was this that then developed into the full title-page, with publication details as well as author and title.”

References and further reading:

Smith, Margaret M. “Title-page” in Michael F. Suarez, S.J. and H.R. Woudhuysen eds., The Oxford Companion to the Book, 2010.

Smith, Margaret M. The title-page: its early development 1460-1510, 2000.

British Library, Catalogue of illuminated manuscripts, 2018