Woodcut printing is a technique that pre-dates the printed book; used for printing playing cards and religious prints, for example, as well as for block books. To create a woodcut image, the artist either drew directly onto a wooden block, or onto paper which was then pasted to the block. This image would then be carved in relief – so that the area to be inked stood out, whilst the white spaces in the finished image were carved into the block.

Whilst the very earliest of books were largely printed without any illustration or decoration – perhaps leaving spaces on the printed page to allow for these to be added by hand – printers quickly realised that woodcut printing offered a simple means to add decorative features and illustrations to texts. Crucially, the fact that woodcut printing was, like movable type, a relief technique, meant that images and text could be set and printed together, on the same sheet of paper. By contrast, intaglio printing techniques – which involve an image being incised into a surface – required a different kind of press (a rolling press) in order to produce an image. As a result, if illustrations produced using intaglio techniques were to accompany text on the same page, the sheet would have to be printed twice – once for text and once for image. This was a timely and a costly process.

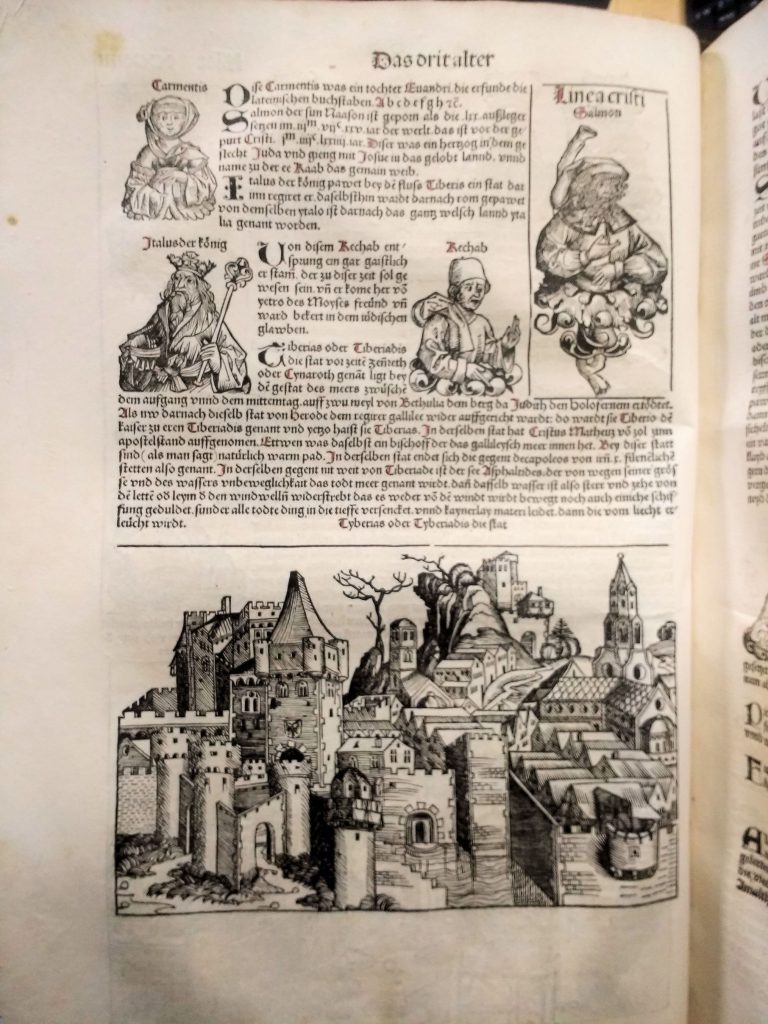

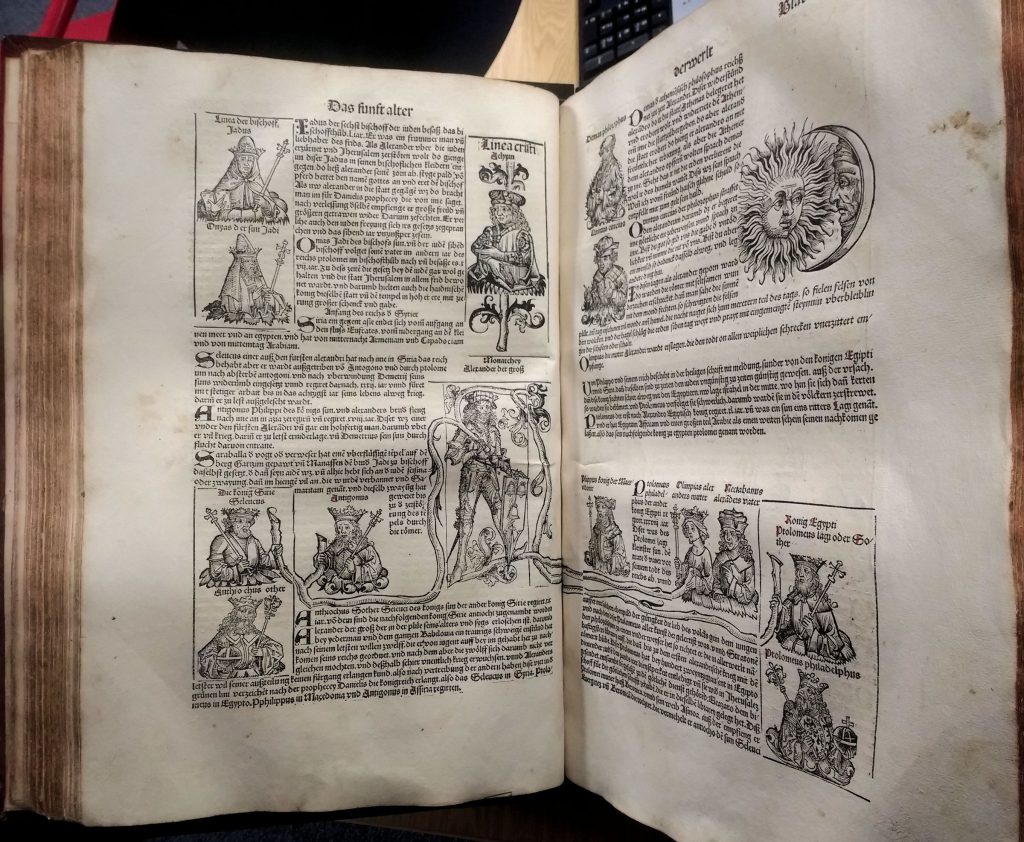

Woodcuts, then, were the preferred method of producing images for early printed books. Earlier in the series we introduced the most highly-illustrated book of the 15th century – the Nuremberg Chronicles – with its 1809 woodcut images, produced using 645 woodblocks. Since woodblocks were durable, it was not uncommon to reuse images – sometimes even in a different work entirely.

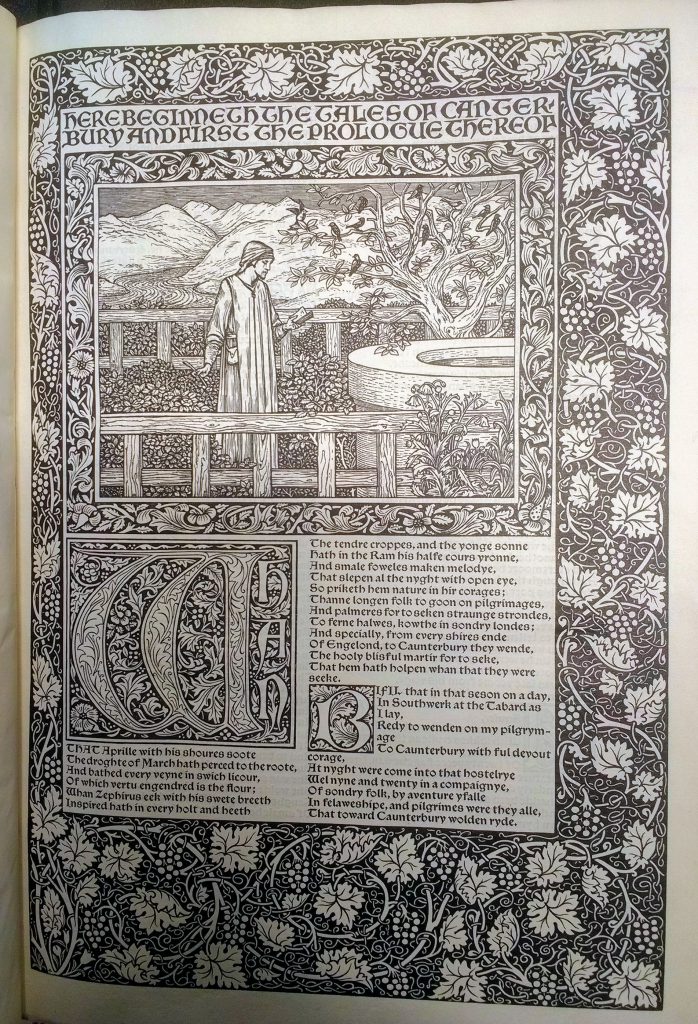

Whilst the earliest woodcut images in books were generally fairly simple, outline images, designed to allow for colouring by hand, by the end of the 15th century the art of woodcut illustration in books had advanced such that the most sophisticated productions displayed considerable artistry, including the use of chiaroscuro effects to produce tones. Still, in terms of the quality of the finished image, woodcut was not able to compete with intaglio methods of printing. It was for this reason that copperplate printing eventually overtook woodcut as the preferred method of illustrating books, by around the middle of the 16th century. Because of the difficulties in printing text alongside copperplate images, it became common for illustrations to take up entire pages, which were then inserted in place before binding. As a result, books generally contained fewer illustrations and decorations than they had during the golden age of the woodcut.

References and further reading:

Hind, Arthur Mayger, An introduction to a history of woodcut, with a detailed survey of work done in the 15th century, 1935

MacLean, Robert, Book illustration: the woodcut, 2012

Suarez, Michael F. and H.R. Woudhuysen eds., The Oxford Companion to the Book, 2010.