How do you imagine yourself, and your community, 10 years in the future? Conversely, looking to the past, how has society changed in ten, twenty, thirty years?

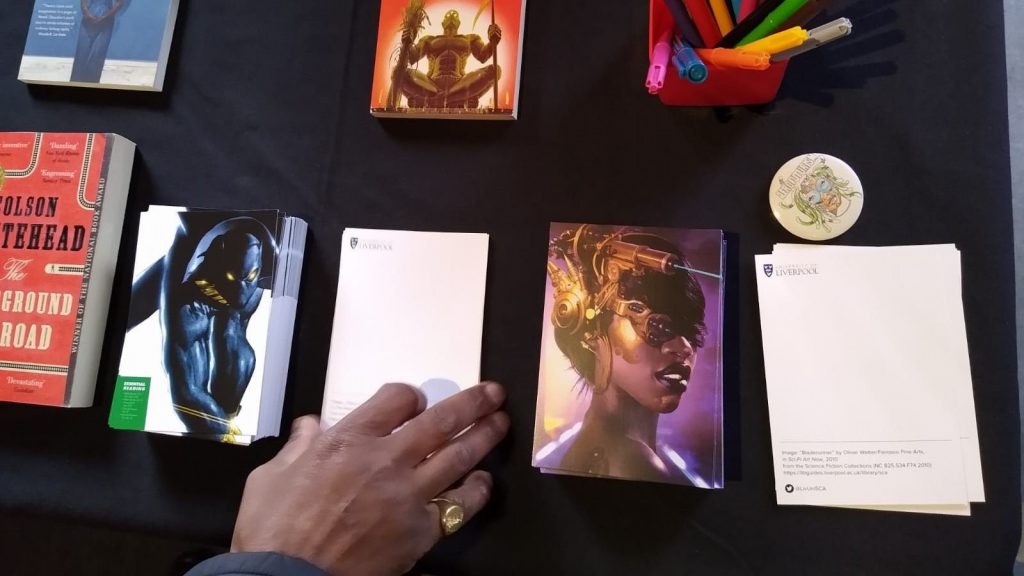

To inspire engagement with these questions, and to commemorate the last day of Black History Month, SCA’s Science Fiction Collections Librarian, Phoenix Alexander, installed a pop-up Afrofuturism library in the International Slavery Museum on October 31st 2019. Collaborating with Adam Duckworth and Mitty Ramachandran, Alexander curated the library to feature Black-authored texts from the SF collections: texts ranging from the Caribbean folklore-based speculative fiction of Nalo Hopkinson to the neo-slave narratives and far-future worlds of Octavia E. Butler. Alongside the books, specially-printed postcards were designed and printed to feature two striking Afrofuturist artworks from items in the SF collections. During the course of the afternoon visitors could write their hopes and aspirations for the future on the back of the postcards, which were displayed on a wall of the museum to create a community archive of sorts.

The term ‘Afrofuturism’ was coined in 1993 by cultural critic Mark Dery and fleshed out in a now-famous 2003 issue of the academic journal, Social Text. In the introduction to this issue, Afrofuturism was defined as any “text and images… [that] reflect African diasporic experience and at the same time attend to the transformations that are the by-product of new media and information technology.” In the preceding decade the term has become short-hand for any speculative ‘text’ – music video, film, novel, or comic – that foregrounds Black characters and communities, from Black Panther to the ‘ArchAndroid’ stylings of musician Janelle Monáe.

The small selection of texts on display at the International Slavery Museum showcased not only the literary works of Black authors but the often-striking artwork that helped to visualize worlds in which historically excluded communities could be seen and considered in narratives of futurity. The library proved particularly popular with younger visitors, who were inspired by the objects to produce their own artwork on an adjacent activity table. On display, too, was an interactive timeline detailing the history of Afrofuturism and Black speculative writing more broadly.

The library was a successful first step in bringing these inspiring texts to a community wider than the University’s walls – but also energized a commitment to giving voice to those communities who have not historically been afforded the kinds of institutional recognition that an academic library provides. Looking ahead, Dr. Alexander hopes to facilitate more events like this in the future and to build on the amazing SF Collections by collecting works by BAME, queer, and disabled authors.

Science Fiction is perhaps the most nakedly political of all fictional genres in that it explicitly renders who has a place in societies in the future – and who is excluded. Afrofuturist texts help make a space both physical – in institutions, in homes, in public spaces – and in the cultural imagination. By reading and enjoying these works, by encountering the physical objects that serve as interventions in new and exciting forms, we shape our own imaginations and, little by little, help to build a better world.