Home to both of the city’s Cathedrals, a concert hall, a theatre and an iconic pub, Hope Street is one of the most vibrant areas of the city. Using material held at Special Collections and Archives to guide us on a virtual tour of Hope Street, we gain an insight into how the street has changed over the past 100 years, and how different the street may have looked if some building plans had been fully realised.

…

At the foot of Hope Street stands Liverpool’s Metropolitan Cathedral, the largest Catholic Cathedral in England.

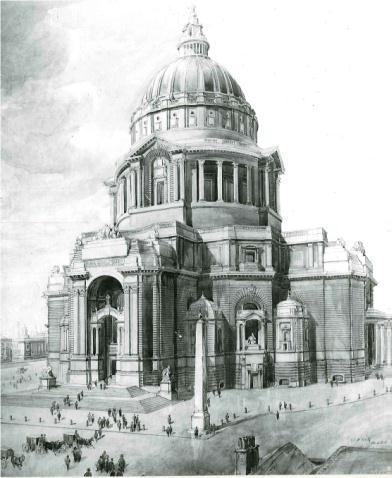

The image above shows the original design for the Cathedral by Edwin Lutyens. Construction began with the building of the Crypt in 1933 on the site of the former work house but, with the onset of WW2, the rest of the Cathedral was never completed and the architect died in 1944.

In 1959 a competition was held for a new design for the Cathedral, the winning piece by Frederick Gibberd being the one we recognise today.

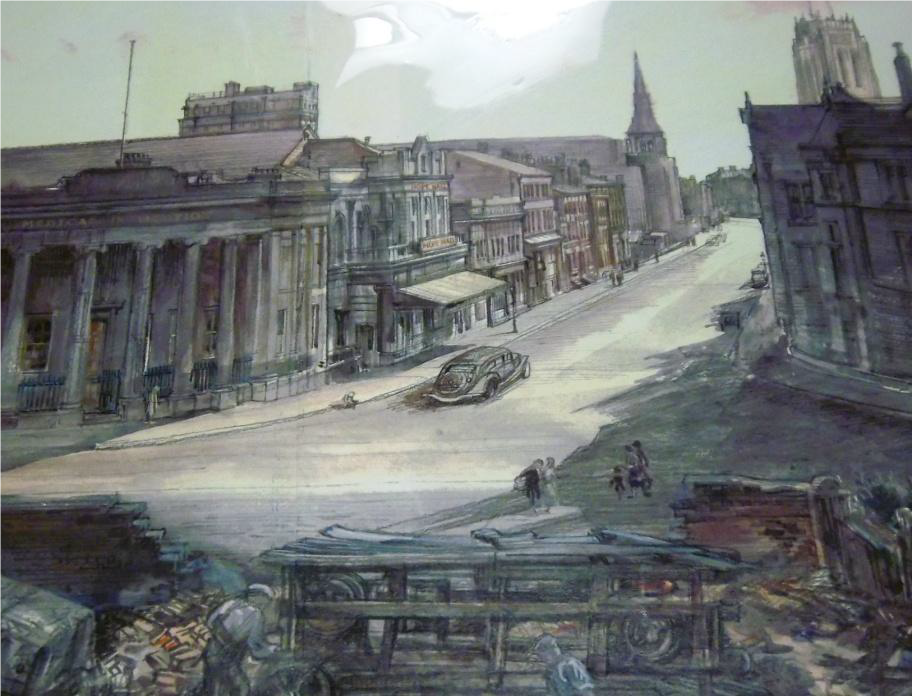

The above illustration by A. P. Tankhard shows how Hope Street may have looked in 1947. Above the motor car in Tankhard’s illustration stands Hope Hall, originally built as a dissenters chapel in 1837. By the time of Tankhard’s drawing the building had been converted to a cinema, and continued to serve this purpose until its closure in 1963. It was then that, having become a magnet for local artists, writers and musicians, a local arts group helped to establish The Everyman Theatre, and a new building was shortly erected.

One of the members of this group, the ‘Liverpool Scene’, was Adrian Henri (1932-2000), poet and artist, whose archive is held at Special Collections. A member of the Hope Street Association – which promotes local businesses, arts, religious and educational organisations – Henri situated many of his poems around the Hope Street Quarter.

“Sunshine,

Extract from poem entitled ‘Alice/Early Autumn’ from the collection Wish You Were Here (SPEC HENRI 13).

overtaken by the shingle-sound

of first leaves along Hope Street

the tinkle of a Coke-can

a black plastic bag

slinks along the gutter.”

Continuing to the corner of Hardman Street, we come to the Philharmonic Dining Rooms, known more affectionately as ‘The Phil’. The pub has recently been upgraded to a Grade I listed building, praised for its “architectural quality and magnificent interior” by Historic England.

Built around the turn of the century by Walter Thomas for brewer Robert Cain, the public house was intended to serve a new class of drinker as part of the new ‘Improved Public House Movement’. Robert Cain wanted to create a drinking establishment that was far removed from the world of the ‘Squalid Liverpool’ drinking den, which was the subject of temperance campaigns in nearby Toxteth and Dingle.

The Quentin Hughes collection contains many photographs and elevations of The Phil. As a half-way point between the Everyman Theatre and the Philharmonic Hall, The Phil served as a central meeting point for musicians and writers alike.

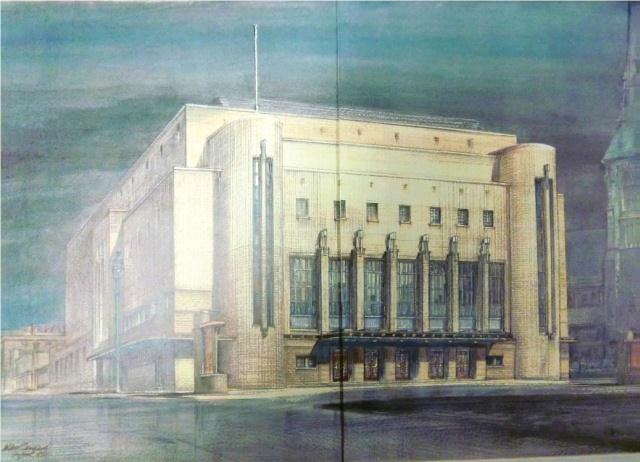

On the opposite corner to The Phil stands Herbert J. Rowse’s Philharmonic Hall, home to the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Society. Built 1936-9, the 1,790 seat Art-Deco hall replaced the previous hall of 1846-9 by John Cunningham which had burned down in 1933. It stands on the old site of William Hope’s house, a merchant who gave his name to the street.

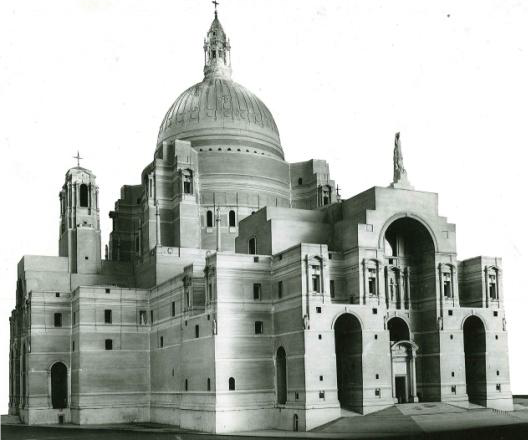

As we finish our tour at the bottom of Hope Street we come to Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral. Following the establishment of a diocese in 1880 a competition was held for the building of a Cathedral near St George’s Hall. However, these plans fell through and a new competition in 1901 was held for a Cathedral based at the site of St James ’s Mount. Sir Charles Reilly (1874 1948), head of the Liverpool School of Architecture between 1904 and 1933 , entered the competition with the classical design you can see in the image below. His plans, amongst many, were rejected in favour of a Gothic revival design by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott. Building commenced in 1904 at the peak of Liverpool’s prosperity but following economic downturns and re-designs it took another 74 years to be completed. Liverpool Cathedral has now been given a Grade I listed status by English Heritage.