Postgraduate students from a number of University of Liverpool courses visited SCA this March as part of a joint workshop on book history and manuscript studies. They were introduced to a variety of manuscripts and early printed books from the collections here, including MS.F.3.13, which lays claim to being the oldest complete work in University of Liverpool’s Special Collections and Archives. Dated by Neil Ker to the 13th century, it was redated in 2013 by medieval manuscript expert Dr. Erik Kwakkel, to the 12th.

With this particular manuscript the student’s focus was on identifying the script, which can provide a clue to the date and place of manufacture of a manuscript. But there is much else about this book that might prove instructional to a budding student of manuscripts.

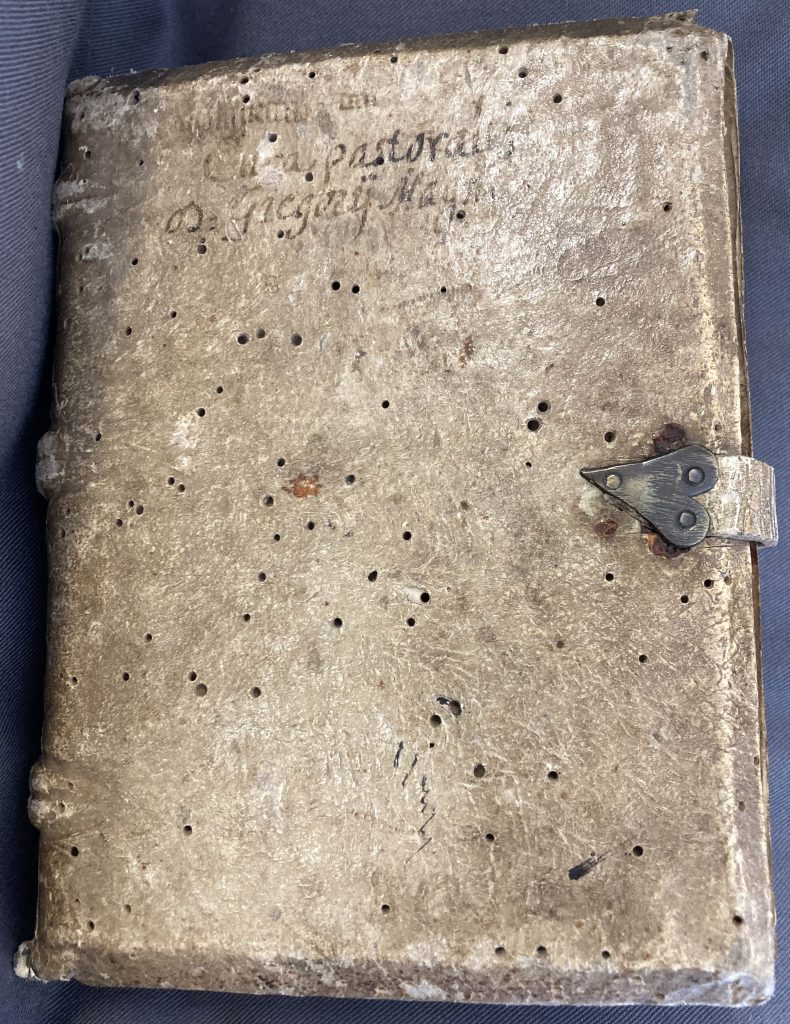

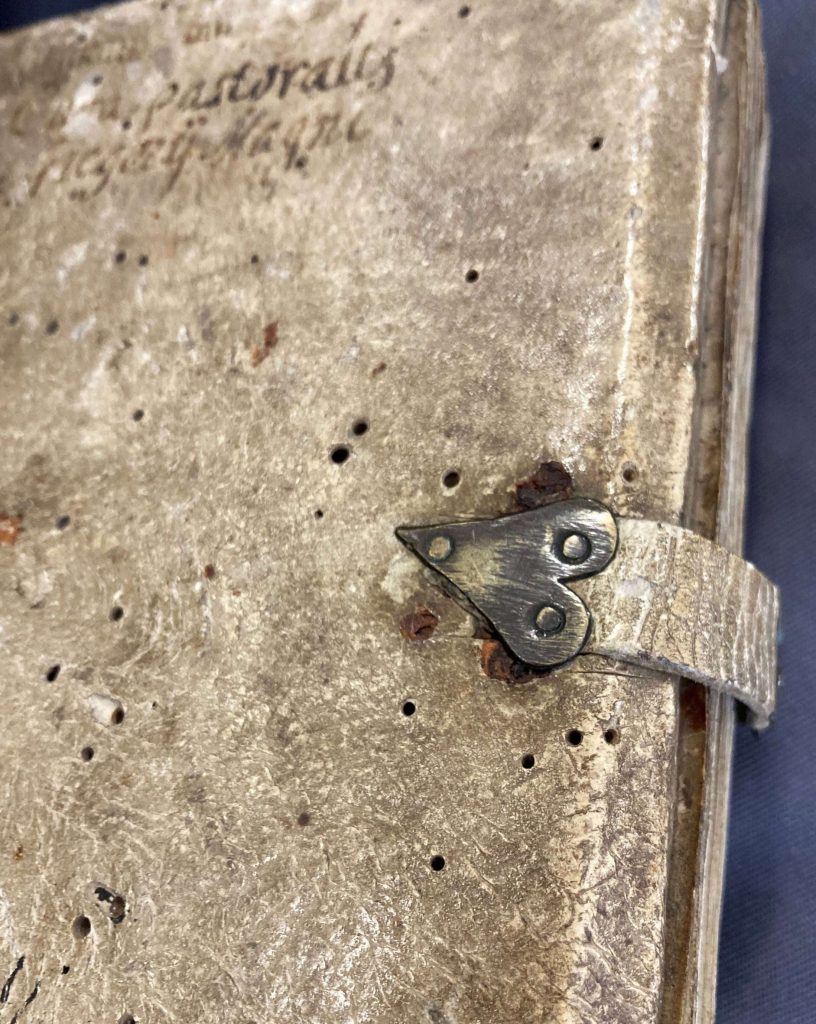

When he visited in 2013, Dr. Kwakkel particularly highlighted the book’s medieval binding as providing modern users with a true sense of the object as it would have been known to its earliest owners. The text, written on leaves of parchment (animal skin), has been given ample protection, sandwiched between two thick wooden boards held firmly closed by a remarkably intact clasp, which begins on the upper board and attaches to the lower by means of pleasingly loveheart shaped fastenings. The weight of this binding plays an important role in keeping the parchment leaves on which the text is written from springing up and curling.

The wooden boards have been covered with pigskin – a tough, long-lasting material. This is a useful clue as to the where the book was bound, pigskin being a covering material used primarily in Northern Europe, and particularly in Germany.

An earlier owner has written the title of the book on the upper cover. The placement of title information helps to reveal the ways in which a book was shelved in the past. For much of the Middle Ages books were stored flat, so writing the title on a cover rather than on the spine was a logical choice.

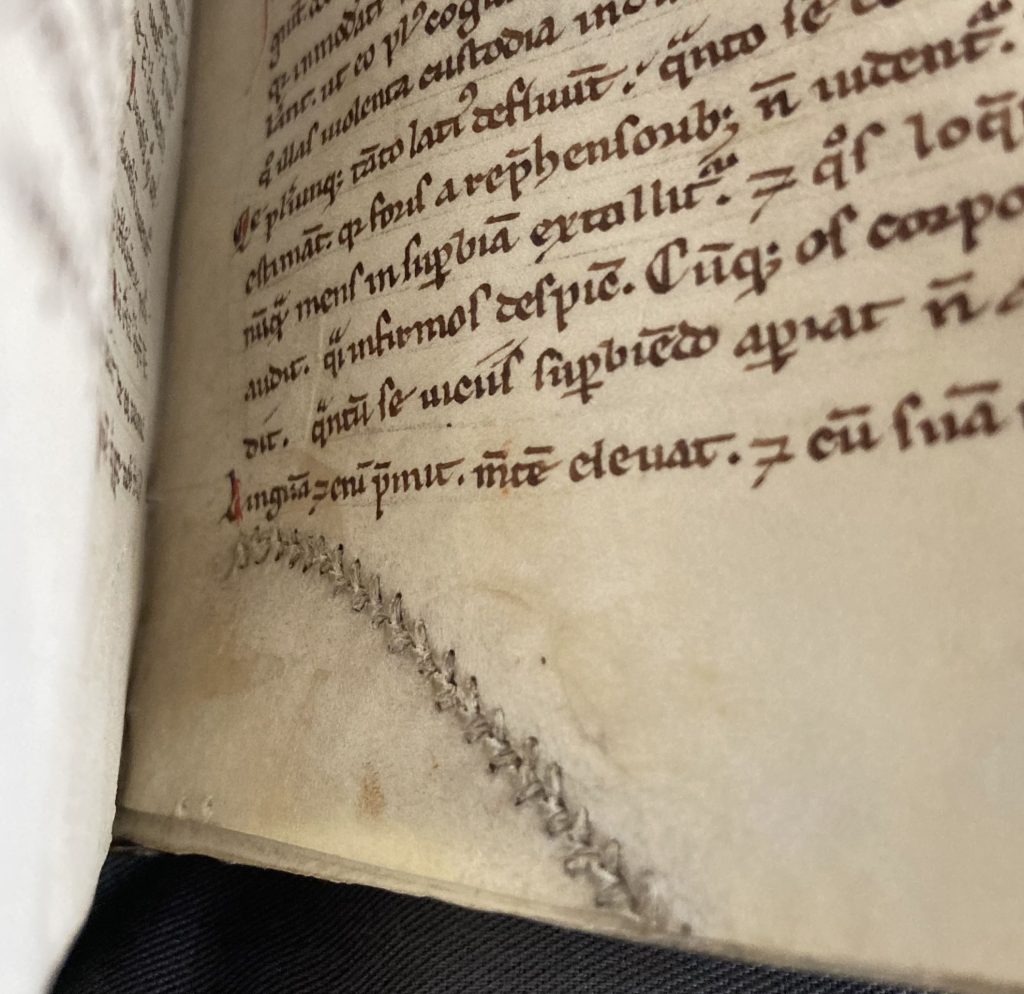

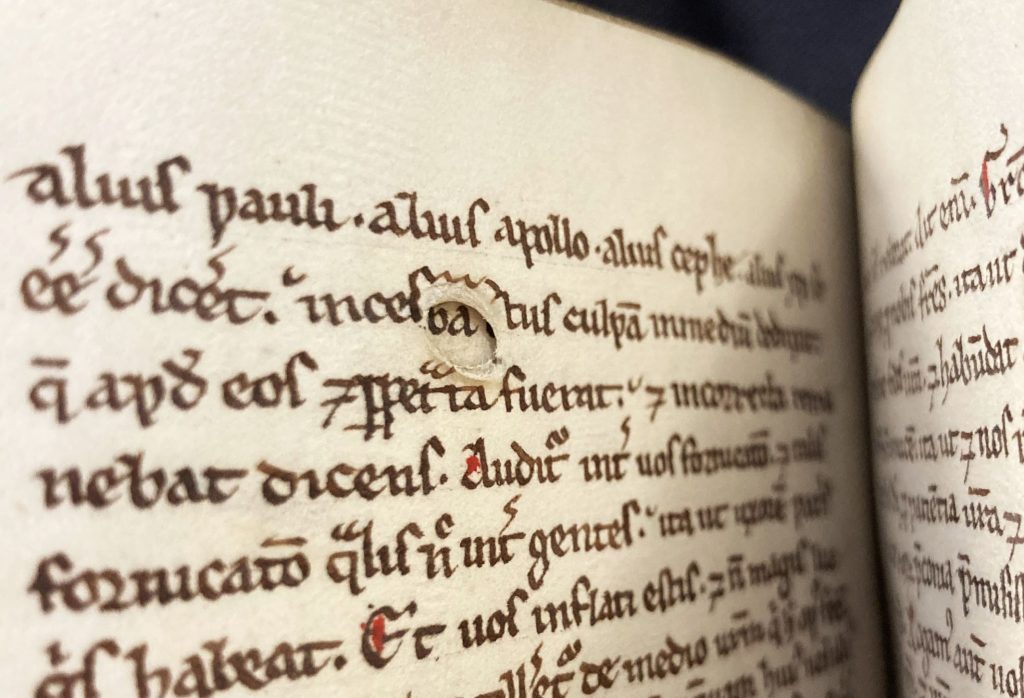

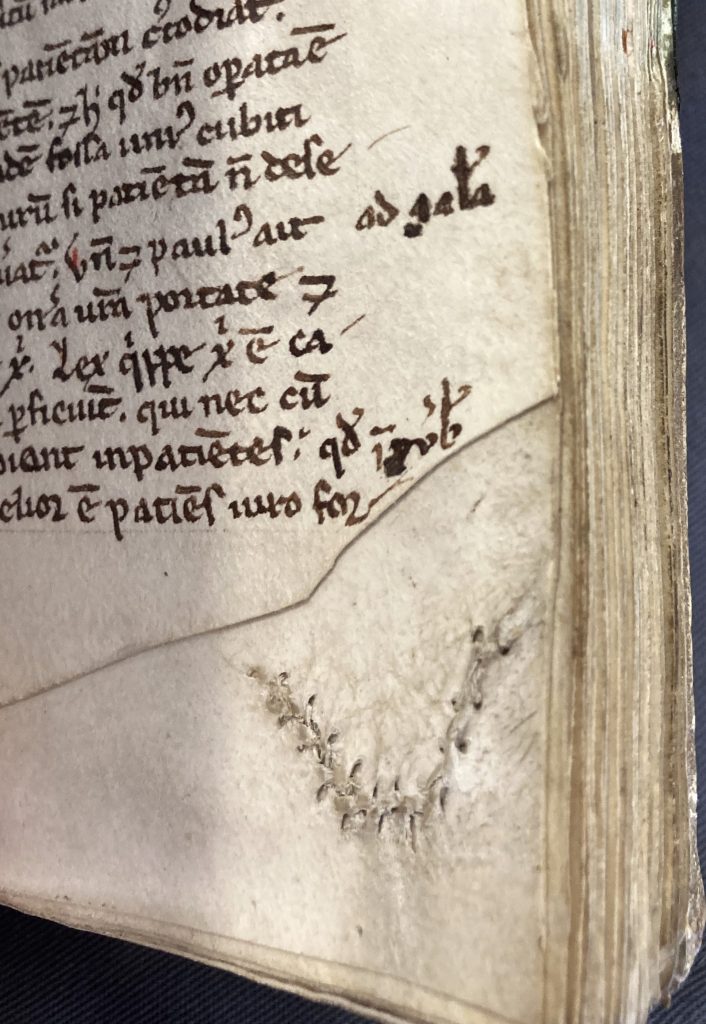

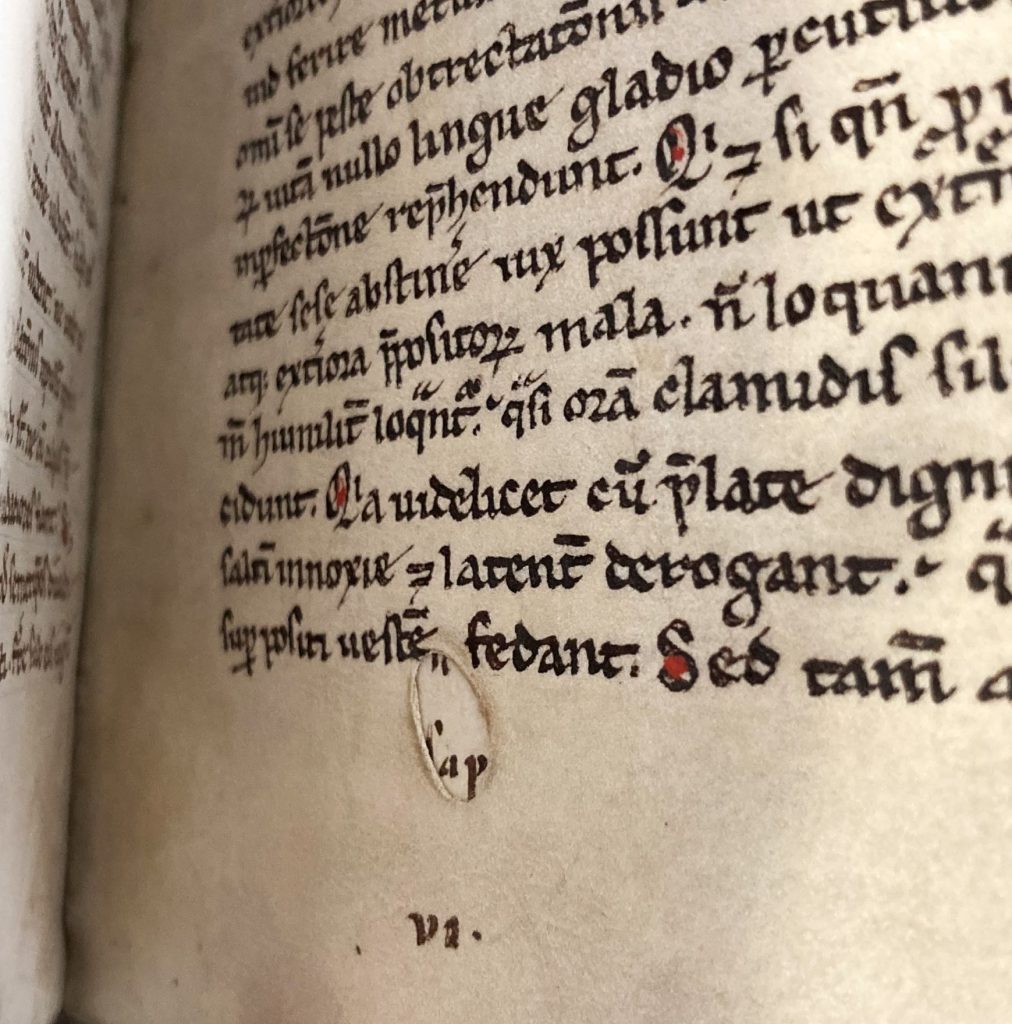

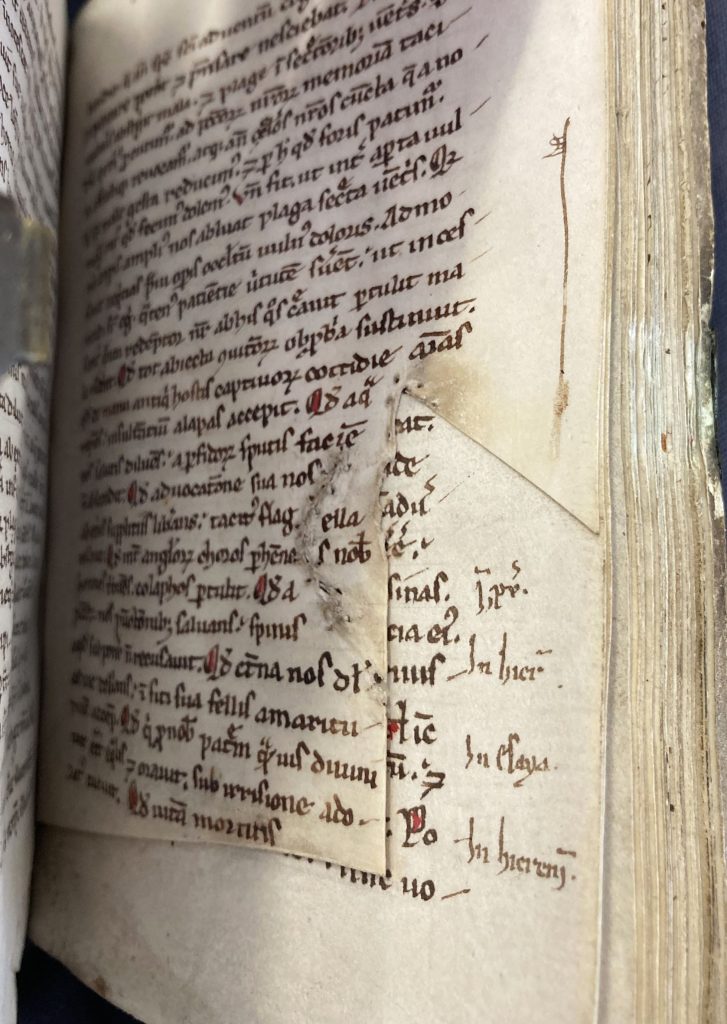

It may be the first time students have experienced a book written by hand on parchment, the writing material on which the vast majority of medieval manuscripts in the Western world were inked. The leaves in this book have features which help to demonstrate the process of making parchment from animal skin. Numerous leaves contain holes formed when the animal skins were stretched and scraped to create a writing surface. Many of these are likely to correspond to imperfections in the animal’s skin; scar tissue from bites or scrapes for instance. Some of the holes have been mended by sewing, and some have been decorated by a playful scribe, who has traced around them.

Some of the leaves of the book have curved rather than square edges which correspond to curved parts of the original skin (a shoulder, or neck line, for example). Imperfectly rectangular leaves such as these were a cheaper option for writing on, and the thickness of the parchment in this book is another sign that economies were made in this regard.

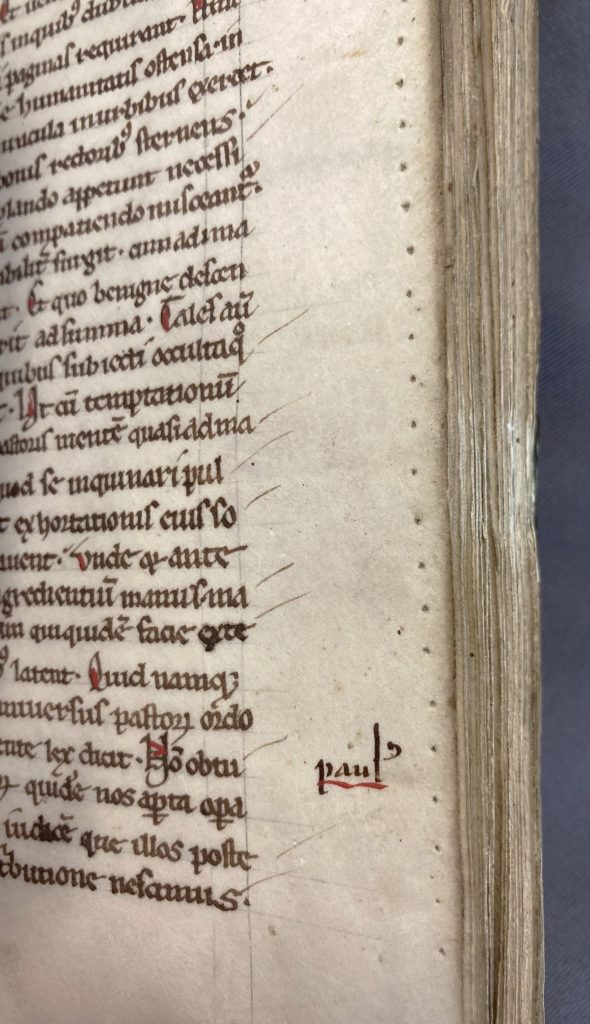

It is not just by the holes in uneven leaves that this book makes plain aspects of its making; it also holds features which can help students to understand the scribal process. The leaves have very clearly visible regular holes in the outer margins, for example. Before the scribe began writing he needed to rule the leaves. To do this, he began by pricking holes in the margins of several leaves at a time. Lines could be drawn between these holes to create straight lines at regular intervals to write on.

And importantly for the dating of this work, the first line of text is written above the top ruled line. As first noted by the aforementioned Neil Ker, around 1240 a shift in scribal practice occurred: from the first line of text beginning above the top line to below it.

The earliest evidence of ownership after the binding comes in the form of an inscription of the Augustinian monastery of St. Pancras at Ranshofen in Austria, which has been dated to the 15th century. The text is a copy of Pope Gregory I’s De cura pastorali – a treatise on the responsibilities of the clergy. The class are encouraged to consider where the books in the class were made and for whom – this being just one example of a book they are shown which has a history of monastic ownership. Monasteries were centres for book making, as well as book ownership.

Overall, MS.F.3.13 manages to be both workaday and exquisite. It is small, portable, built for handheld consultation. Despite its diminutive size (the book measures 16.5 by 12 cm), thick wooden boards and thick parchment sheets give this book a heft and a presence; unlike consulting a screen, reading this book is a markedly physical experience. The book makes an impression on its reader as an object, as well as for the text it carries. The thick, uneven leaves are riddled with imperfections. They are not flush with the boards but instead protrude ever so slightly beyond their covering, and no effort has been made to hide the pricking holes by trimming the leaves, suggesting somewhat different aesthetic expectations to those of someone purchasing a book today. Indeed, every aspect of this book’s production speaks of careful and time-consuming labour: from the small, neat handwriting, to the thick sewing supports, bevelled boards and heart-shaped clasp. That the binding is in-tact after so long is no doubt an indication that this little book has been treasured and treated with care by generation upon generation of owner. It is satisfying to see it continue to be used and learnt from by students today.