This week marks the centenary of the one hundredth week of fighting in the First World War. At this point, hopes of an early curtailment might well have rescinded in the face of the on-going reality.

It seems appropriate at this point to break from the customary format of our This Week’s War asides with a closer look at the source materials.

We are fortunate to have a range of sources, both primary and secondary, to draw upon each week. This, we hope, enables us to capture poignant and pertinent images of the war as experienced by those both on the frontline and watching events unfold at a distance.

Of the former category is a letter from the Cunard Shipping Line archive. Captain W. Turner captained the Cunard vessel RMS Lusitania for what was to be its final voyage, during which it was torpedoed by a German submarine on 7 May 1915. In a letter to a Miss Brayton, dated 10 June 1915, Turner expresses his sorrow and regret over the loss of life:

I am thankful to say that I have not felt any bad effects from my terrible experience, but I grieve for all the poor innocent people that lost their lives and for those that are left to mourn their dear ones loss. Please excuse me saying more, because I hate to think or speak of it.

[D42/PR13/29]

His request that Miss Brayton pardon his brevity is an indication of the horror experienced by those who bore witness to the disaster first-hand.

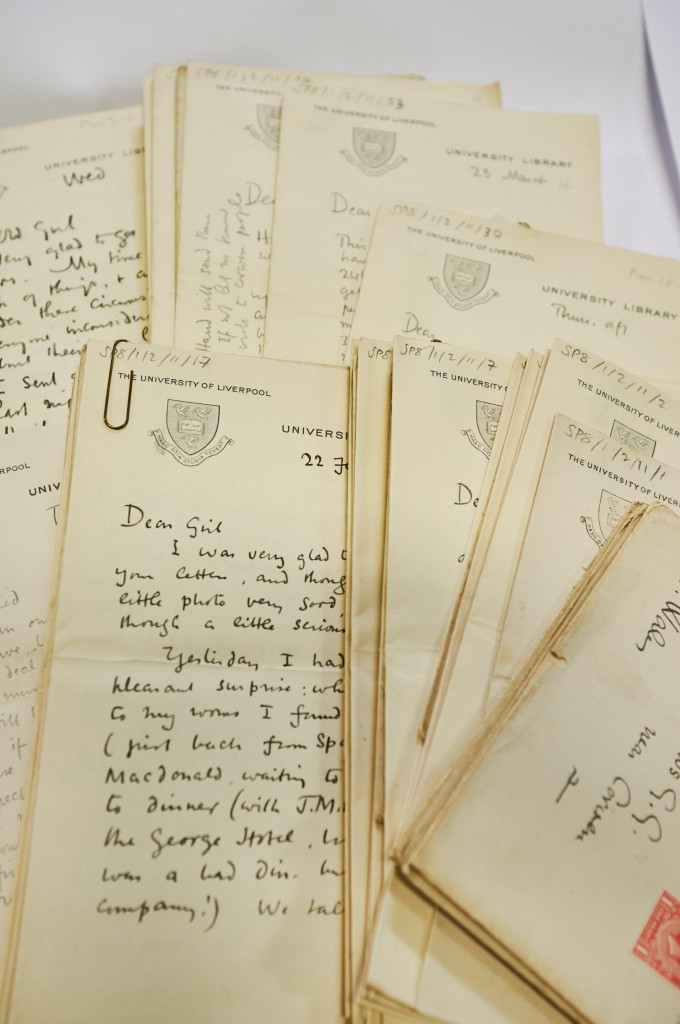

Primary sources offering the home front perspective include the letters of former University of Liverpool Librarian John Sampson, whose letters to his wife, Margaret, detail the correspondence he receives from his son Michael, serving with the British military, along with Sampson’s own reflections on this familial connection to geographically distal events. In May 1916 Sampson writes to his wife:

It was a surprise and a little shock to get Mick’s line this morning saying that he is indeed “overseas”. I thought it would come. It is hard to realize exactly how one feels about it. If one says, “It is a happy thing and a relief that Mick’s ability and application which got him his ‘D’, should now, without his seeking for it or anything outside the immediate duty, carry its reward by setting him free from the chances of war that wait far less happy and gifted boys”, it is only putting one side of the case. And one’s mind, once made up, is made up to all. I hope that he will be spared. But whatever comes Mick will have done well.

[John Sampson Archive: SP8/1/2/11/39]

An alternative account of wartime Britain is recorded in the diaries of John Bruce Glasier, socialist and pacifist. This account offers no jingoism or appetite for the war. Rather, Glasier documents his and his associates’ political activities (Glasier and his wife, Katharine, were founder members of the Independent Labour Party in 1893) along with the struggles faced by conscientious objectors. From December 1915:

Mr Asquith has decided to bring in a bill to conscript the unmarried men who have not “attested” under Lord Derby’s scheme. This is a thunderbolt. We all believed that the Derby scheme had at any rate indefinitely postponed conscription. The thought of Britain having recourse to this worst of all tyrannies, makes me sick at heart.

[Glasier Papers GP2/1/22]

Though they cannot be mined for quotations, these diaries’ blank spaces are almost as poignant as the entries themselves. Glasier was in very poor health, and many of his entries reveal just how badly his health had declined and how much discomfort he was in by mid-1916. Often such entries are followed by prolonged periods where he does not write, and the present-day reader can only wonder whether he lacked the physical strength or motivation to record his experiences.

The collection of First World War pamphlets has augmented the series with excerpts of secondary narratives, reports of media commentary, and propagandising from both sides. Of especial interest is the series of Foreign Intelligence reports, which bear the express warning that their contents are top secret. One such report from December 1915 publishes an exhortation, printed in the German publication Zukunft, for German citizens to recognise the strength of the Allied Forces’ conviction, and the inevitability of a protracted and bloody war of attrition:

Not one of our enemies has laid down his arms. Not one is discouraged, no one doubts the final victory, and they are all determined to make every effort to obtain it. It will, therefore, be a war of exhaustion of which no human eye can see the end. All Germans must be made to understand this.

[POV X 44.11.6(1)]

The autograph diaries of Alfred Osten Walker, President of the Liverpool Biological Society from 1892-3, demonstrate the disjuncture between the daily routine and the interpositions of the war. Walker’s entries juxtapose the military and the mundane, reflecting the war as experienced by those whose frontline experience came vicariously through press and officialdom. An entry from October 1915 reads:

Mrs Bonasted called p.m. and had a game of G.C. Rather dull and foggy. Wind W.

Heard that a Zeppelin on Wednesday night dropped a bomb on a camp of Canadians at Sellindge and killed 12.

[Liverpool University Library Manuscripts LUL MS9 1915]

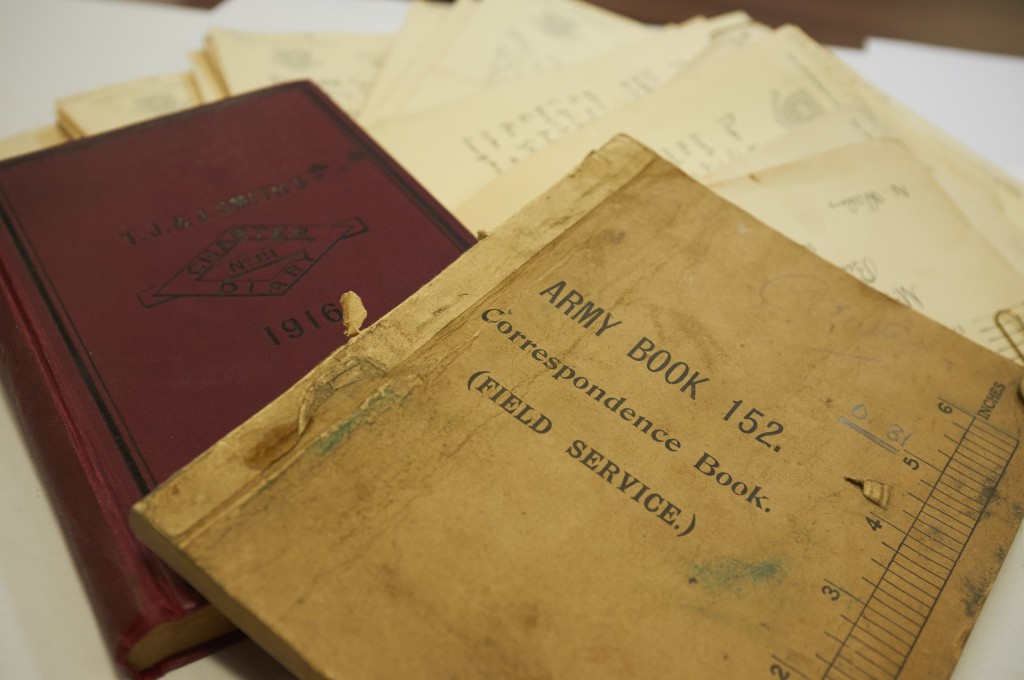

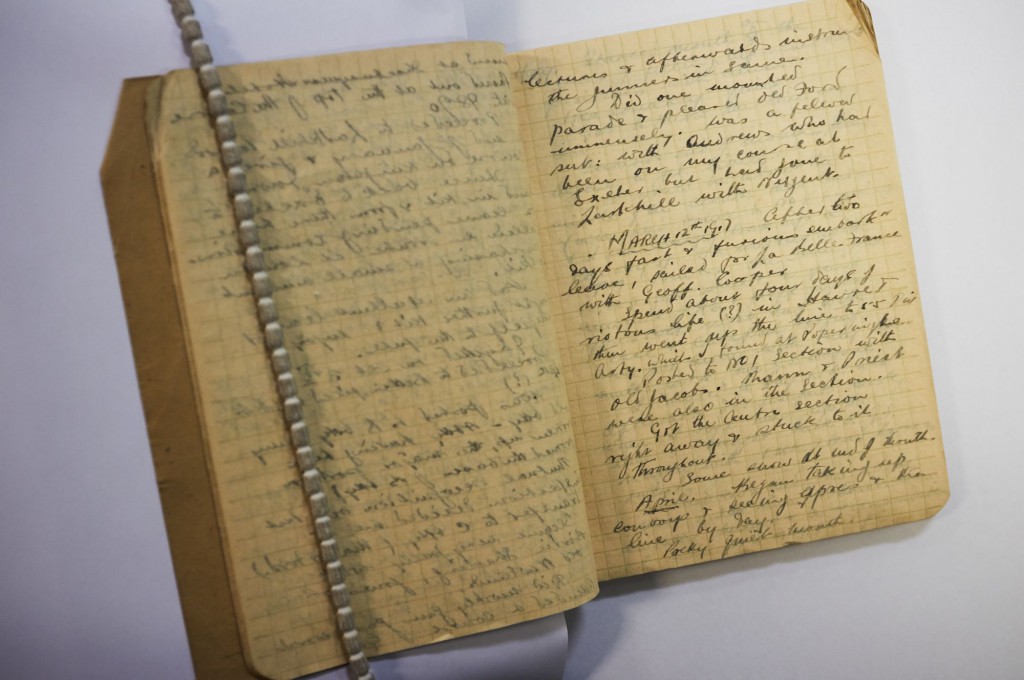

Manuscripts, of course, frequently present the additional challenge of deciphering the author’s handwriting. Such was the palaeographical challenge with the military service diary of former University of Liverpool professor, Charles Wells:

Events which the intervening years have elevated to especial infamy – the sinking of the Lusitania, the Battle of Jutland, the Act of Parliament enforcing military conscription, or the horror of the Somme trenches – are typically easier to source quotations for, given the flurry of contemporaneous news reportage and commentary each provoked. These events become the points of entry in to the archives and printed collections, while periods of lesser historical infamy are accessible through more generic war-related keywords combined with a date range.

From a professional perspective, to find a pithy remark encapsulating one of the most infamous events in twentieth-century military history is incredibly satisfying. From a human perspective, it is sometimes slightly disconcerting. These events are brought to life; they shown to be far more than points on a textbook timeline.