The next day was Sunday, and I had it all to myself; and now, thought I,

my guide-book and I shall have a famous ramble up street and down lane,

even unto the furthest limits of this Liverpool.

Herman Melville, Redburn: His First Voyage (1849), chapter 31.

…

This post will explore the historic travel guides for Liverpool held in Special Collections and Archives (SCA) as part of the “New Worlds” series for the Institute of Historical Research’s History Day 2020.

Visiting a new geographic area, foreign to the individual traveller, can elicit responses of trepidation and joy. As such, historic travel accounts often provide interesting insights into countries and cities from “fresh” eyes. But historically it was often the help of a trusted guide, either a friend or printed text, which would lead and encourage the traveller in exploring a new world.

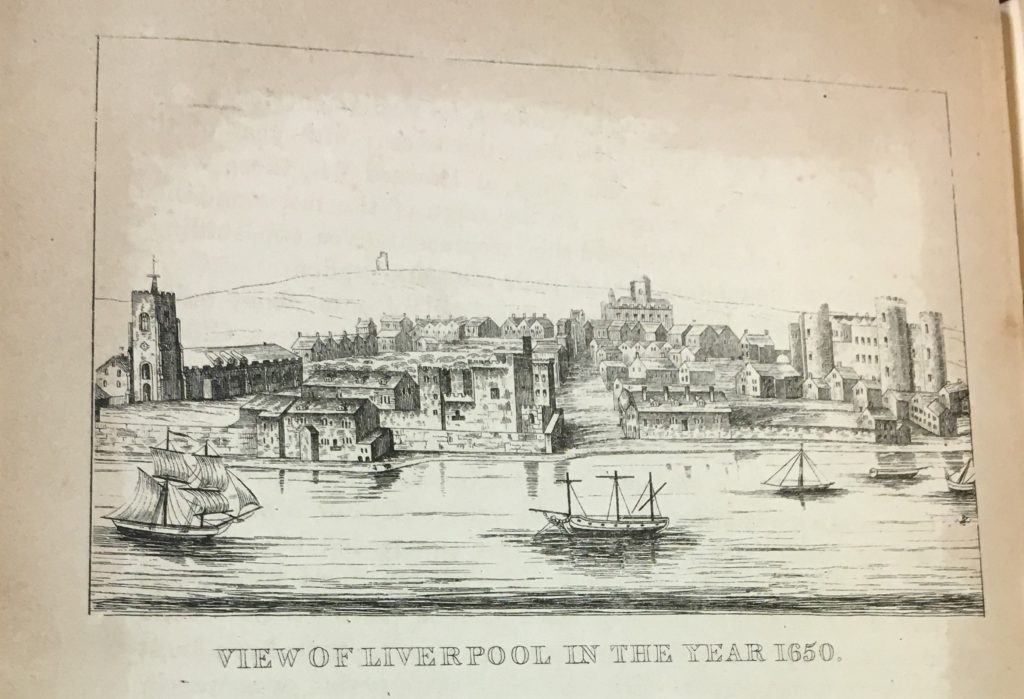

Guidebooks to Liverpool first appeared in the late 18th century. The target market for the Liverpool guidebook was the gentleman, whether that be a local or a visitor. The guidebooks purpose was to be not only a functional guide in the day-to-day investigation of the city, but to demonstrate Liverpool’s importance as a thriving port city.

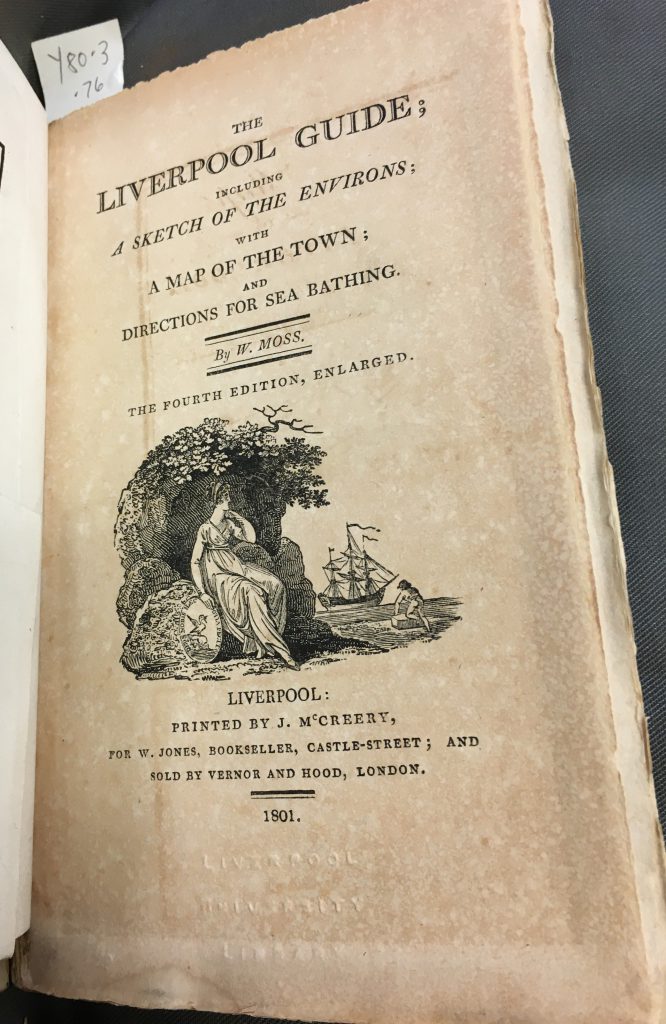

One of the first guides was William Moss’s The Liverpool guide (1796). Moss, a medic, gives the the expected overview of the local sights, including markets, taverns, charities and theatres; however, the volume finishes with directions for the newly-popular practice of sea-bathing, for which the author recommends Liverpool, Runcorn and Bootle.

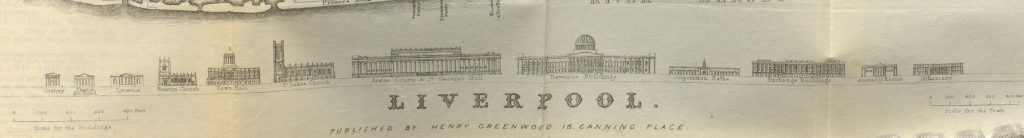

Through the 19th century, guides were produced in increasing numbers but decreasing size, to become a portable “pocket companion” for visitors. The accompanying maps and plans, often sold separately, chart Liverpool’s growth and development.

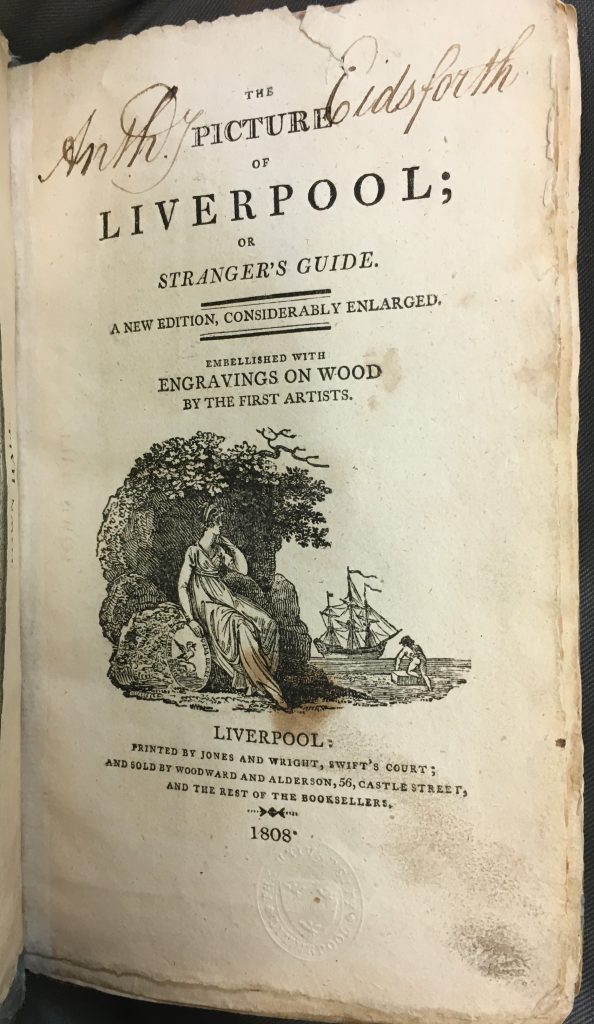

The guide book The picture of Liverpool, or stranger’s guide first appeared in 1805. It begins with the below prologue attributed to “Dr Aikin”, most likely the writer and surgeon John Aikin (1747-1822). Written for the opening of the Theatre Royle in Liverpool in 1772, it paints a romantic yet solemn picture of the river Mersey and the local fishing trade:

Where Mersey’s stream, long windin o’er the plain,

Pours his full tribute to the circling main,

A band of sisters chose their humble feat;

Contended labour bless’d the far retreat;

Inur’d to hardship, patient, bold and rude,

They brav’d the billows for precarious food:

Their straggling huts were rang’d along the shore,

Their nets and little boats their only store.

The picture was unusual in that as well as emphasising the positives of the city, it highlighted the problems. Growing pauperism is attributed to the poor Irish migrants in the city; similarly, the 1833 edition of The Picture acknowledged that Liverpool had profited from the “nefarious” slave trade and was now focused upon the “respectable and honorable” commerce of merchandise goods.

The picture featured in the semi-autobiographical novel Redburn: His First Voyage by the American author Herman Melville (first published in 1849). Chapter 30 details the protagonist, Wellingborough Redburn, reading through his father’s guidebooks before embarking upon a voyage from New York to Liverpool. It is The picture of Liverpool which is explored in the most detail; by considering the lines drawn upon the fold out map, the young Redburn follows his father’s exploration of the unknown city (which he later retraces in person during his time in the city):

Traced with a pen, I discover a number of dotted lines, radiating in all

directions from the foot of Lord-street, where stands marked “Riddough’s

Hotel,” the house my father stopped at.

These marks delineate his various excursions in the town; and I follow

the lines on, through street and lane; and across broad squares; and

penetrate with them into the narrowest courts.

By these marks, I perceive that my father forgot not his religion in a

foreign land; but attended St. John’s Church near the Hay-market, and

other places of public worship: I see that he visited the News Room in

Duke-street, the Lyceum in Bold-street, and the Theater Royal; and that

he called to pay his respects to the eminent Mr. Roscoe, the historian,

poet, and banker.

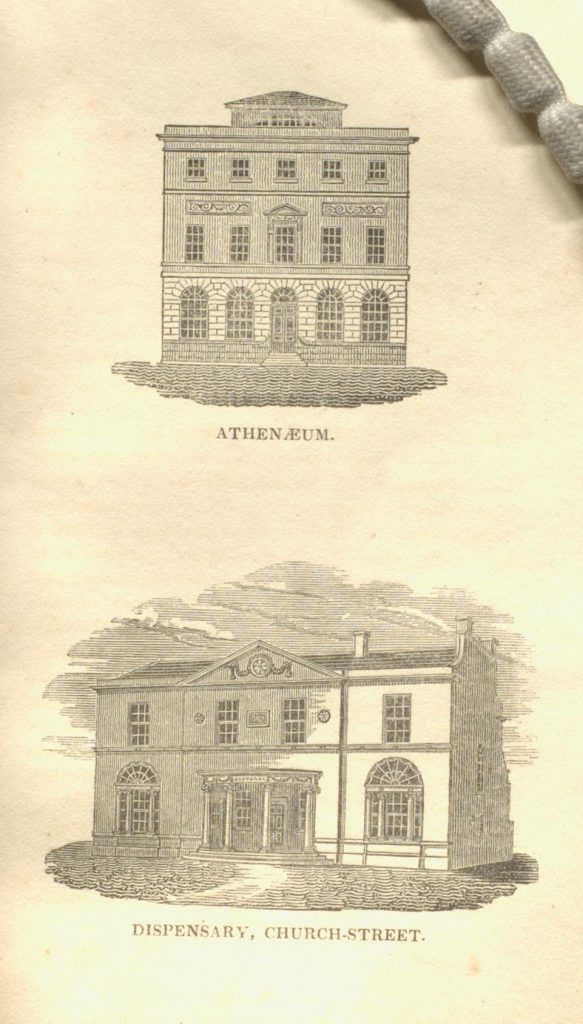

The stranger in Liverpool, first published 1807, became the most popular guide in the first half of the 19th century, running to 12 editions up to 1846. Companion volumes of plates, Views in

Liverpool and its vicinity were published separately. It provides a very buoyant and positive view of the city.

The University’s copy of the 1825 edition of The stranger in Liverpool has a note from its first owner “Dawson Turner; bought at Liverpool, Sep. 25, 1827”. Turner (1775-1858) was a Norfolk banker, botanist and antiquary but had family connections in the area: his son-in-law was Bishop of Chester, and his son, Dawson William Turner, headmaster of the Royal Institution School, Liverpool.

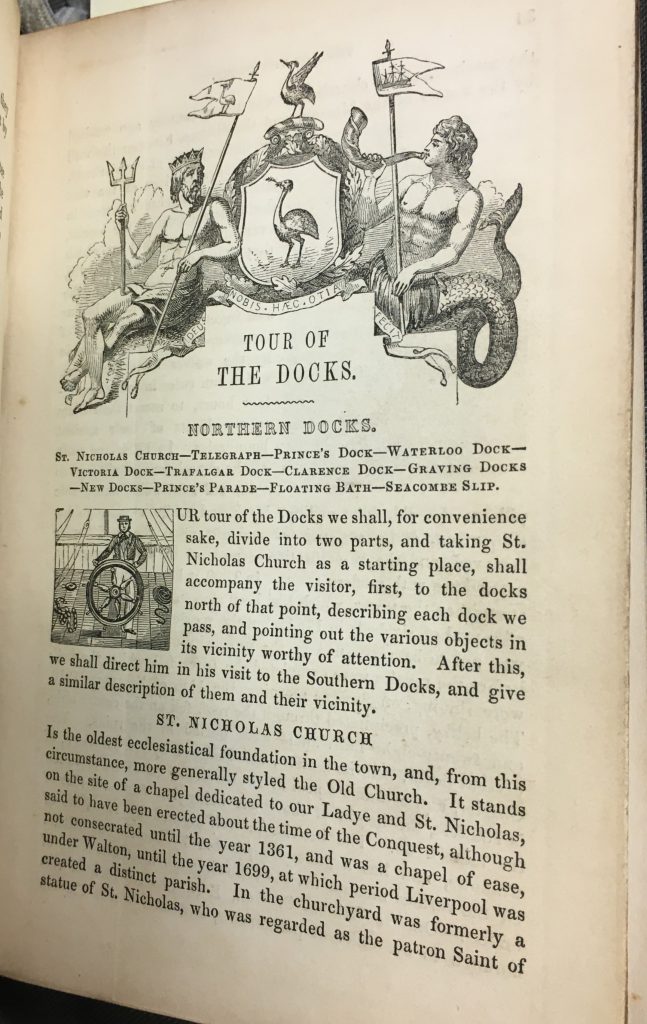

In the 1840s the Liverpool guidebook market expanded with the introduction of The picturesque handbook to Liverpool, which first appeared in 1842. In the competitive market the publisher advertised the work as a successor to The stranger in Liverpool and the bulk of the text is dedicated to various detailed walks through the city centre. It was steeped in pride for the city. Echoing Moss’s work (although without the emphasis on bathing) it featured excursions further afield, including directions for a day at Birkenhead.

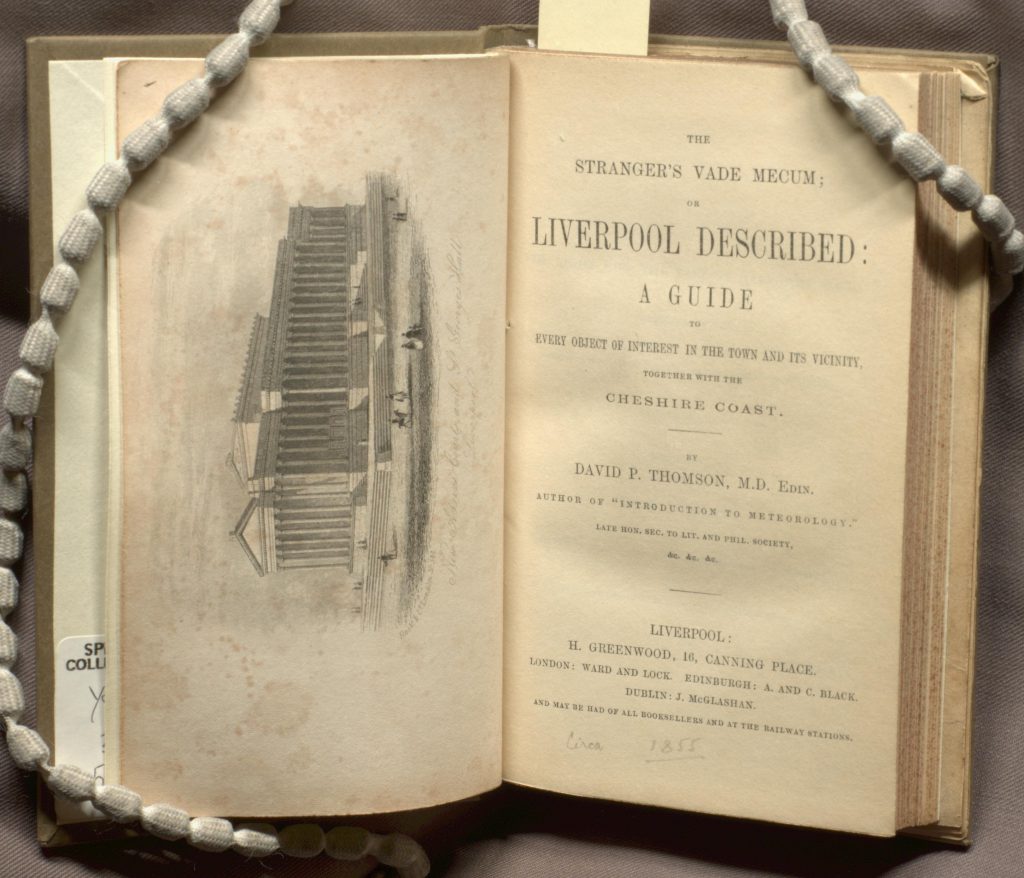

Occasionally specialised guides may be produced for a specific audience visiting the city. The stranger’s vade mecum by Dr David Thomson was published for the British Association for the Advancement of Science who met in Liverpool in 1854. The book encouraged the conference delegates to walk Liverpool and see more than just St. George’s Hall, where the conference was being held. The main theme running through the text is social improvement, as Thomson focuses upon the progress made in the city’s hygiene and sanitation practices.

19th century Liverpool, as a commercial powerhouse and port city, was a “new world” for many of it’s visitors. Armed with a guidebooks, the gentleman visitor would find the unknown terrain easier to explore and (in line with the hopes of the authors of the said books) appreciate the features of a progressive city.

Class marks

The Liverpool Guide: SPEC Y80.3.76 (1801 copy)

The picture of Liverpool: SPEC J24.44 (1808 copy)

The stranger in Liverpool: SPEC J24.52(1) (1825 copy); SPEC Y82.3.1582 (1829 copy)

The picturesque hand-book to Liverpool: Children EIII:21 (1842 copy); SPEC Y84.3.1475 (1846 copy).

The stranger’s vade mecum: SPEC Y85.3.534 (1855 copy)

References:

John Davies, ‘Liverpool guides, 1795-1914’, Transactions of the Historical Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, vol. 153 (2004).

David Seed (ed.) American Travellers in Liverpool (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008)